- Submissions

Full Text

Investigations in Gynecology Research & Womens Health

Knowledge of Obesity Risks and Women’s Health: What do we know?

James KS1*, Matsangas P2 and Connelly CD1

1Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science, University of San Diego, USA

2Operations Research Department, Naval Postgraduate School, USA

*Corresponding author: Kathy S James, DNSc, FNP, FAAN, Associate Professor of Nursing, University of San Diego, Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science, Beyster Institute for Nursing Research 5998 Alcalá Park, San Diego, CA 92110-2492, USA, Tel: 619890-1244; Email: kjames@sandiego.edu

Submission: July 27, 2017; Published: August 18, 2017

ISSN: 2577-2015Volume1 Issue1

Abstract

Background: Even though aware of cardiometabolic risks associated with obesity, health professionals and women are less knowledgeable about the association between obesity and breast/endometrial cancer, and obesity and reproductive outcomes.

Objective: To assess knowledge of the cardiometabolic, general, and reproductive risks associated with obesity in a diverse population of women.

Methods: A convenience sample (N=121 women) completed the study survey.

Results: Participants were less knowledgeable about the effect of obesity on reproductive outcomes (39.9%) compared to general health outcomes (59.2%). Higher education and increased income were associated with increased awareness. Older participants were more aware about the effects of obesity on general health and cardiometabolic outcomes.

Conclusion: It is important to improve awareness on the risks of obesity to reproductive women. Public education focused on the effects of obesity on reproductive outcomes may lead to behavior change, decrease health risks, and save medical costs.

Keywords: Cancer risks; Health habits; Women’s health; Obesity risks

Abbreviations: BMI: Body Mass Index; OHKQ: Obesity Health Knowledge Questionnaire; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; KOA: Overall Knowledge of Health Outcomes; KGH+CM: General Health and Cardiometabolic Outcomes; KR: Reproductive Outcomes; M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation; GH: General Health; CM: Cardiometabolic

Introduction

The health of women is of critical importance, both as a reflection of the current health status of a large segment of the population and as a predictor of the health of the next generation. It is well documented that obesity is a global public health problem. Notably, over the past 40 years, obesity has more than doubled among women [1]. Based upon a nationally representative survey of adults in the United States, the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity in 2013-2014 was 40.4% among women [2]. The researchers’ further note when looking at trends over time from the year 2005 to 2014, there were significant and steady increases in the number of American women who were very obese [2].

Extant research indicates obesity increases cardiometabolic, cancer, and reproductive risks for women [3-6]. Data show there is well-recognized public awareness of cardiometabolic conditions [7]. In contrast, there is a more limited awareness of weight associated cancer and/or reproductive health risk. In fact, according to a cancer awareness study conducted by the American Institute for Cancer Research, only half of Americans surveyed know obesity is one of the most significant factors that increases risk of cancer [8,9]. Yet, excess body fat has been clearly linked to 11 cancers: colon, rectum, endometrium, breast, ovary, kidney, pancreas, gastric cardia, biliary tract system, and certain cancers of the esophagus and bone marrow [10]. Arnold et al. [3] point out a longer duration of overweight is significantly associated with incidence of obesity related cancers. Although not fully understood, having excess body fat has been linked to higher insulin levels, higher estrogen levels, and increased inflammation which can affect cell division. Given the significant number of overweight individuals and risk for chronic disease, this lack of awareness is a concern.

Cardozo et al. [5] recruited women from an infertility clinic to assess their knowledge of reproductive outcomes affected by obesity. Findings indicated limited knowledge on obesity and risk for endometrial cancer (20.7%), stillbirth (22.7%), birth defects (29.3%), breast cancer (38.7%), and cesarean section (48.7 %). In the same sample, women reported greater knowledge regarding risk for miscarriage (60.7%), irregular periods (70%), and infertility risk (82.7%). Results from a prospective survey conducted in the Midwest by Cardozo et al. [7] examining women’s obesity knowledge identified there was limited awareness about female health conditions and the relationship with obesity. Approximately 18% were aware of endometrial cancer, 14.1% stillbirth, 23.7% birth defects, 28.0% breast cancer, 30.8% cesarean section, 33.9% infertility, 35.8% irregular periods, and 37.5% increased risk of miscarriage contrasting to their well-recognized awareness of cardiometabolic conditions. Overall, there is a paucity of studies that have assessed patient understanding and awareness of risks as they pertain to women’s reproductive health. Even the Weight of the Nation public awareness campaign provided limited information on reproductive consequences of obesity.

Data indicate both health professionals and women are well aware of cardiometabolic risks associated with obesity [11-13], and although slowing increasing over the past decade, less awareness continues to be noted for general and reproductive health risks associated with obesity. Despite the comprehensive campaign to focus the public’s attention on the obesity crises, studies show primary care practitioners assessment and behavioral management of overweight and obesity is minimal relative to the magnitude of the problem [14-17]. Time constraints and complexity of patients seen in primary care are often identified as barriers to providing adequate health promotion with patients [18]. Understanding women’s knowledge of weight and associated risks are key to tailor efforts in educating patients regarding the potentially serious risks of obesity on their health and support them in their weight management efforts. The population of women seeking weight management services is of interest because one may assume they represent a knowledgeable and highly motivated group to engage in change. The purpose of this study was to examine women seeking weight management services knowledge of cardiometabolic, general, and reproductive health risks associated with obesity.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional design with purposive sampling of women (N=121) were recruited and enrolled, April to November 2016, from a community based primary care weight management clinic located in southern California. The clinic is a walk in, fee for service clinic operated by an internal medicine physician, adult and family nurse practitioners, and two medical assistants. Weekly weight counseling is received for fee for service. Participation was limited to English speaking, non-pregnant women of all ages who attended the clinic. No specific Body Mass Index (BMI) was set for inclusion in the study as the education is important to all women. We chose not to limit age given the importance of assessing and sharing the risk information across the life span. All procedures were approved by the appropriate administrative and university institutional review boards for the protection of human subjects.

After signing informed consent, participants completed an on-line or paper survey to assess their knowledge on the health risks of obesity. The questionnaire was developed by investigators at the Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago based on current literature and terminology from the World Health Organization, and the known effects of obesity on health [5]. The Obesity Health Knowledge Questionnaire (OHKQ) assessed 3 principal components: self-perception of height and weight; knowledge of BMI; and knowledge of the effects of obesity on general, cardiometabolic, and reproductive health outcomes. Participants’ knowledge of the relationship between excess weight and various health outcomes was assessed by asking, “Does excess body weight (weighing more than you should) increase the risk of the conditions listed below?” Response choices included “yes,” “no,” and “not sure.” Conditions not associated with obesity, such as eczema, lactose intolerance, and tuberculosis, were added as distractors. Participants who responded “yes” (that excess weight increased the risk of the condition) were considered as having knowledge that obesity is associated with an increased risk of that condition Cardozo et al. [5].

Data analysis

>BMI values and adult obesity groups were calculated according to standard convention of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). To assess knowledge of the association between obesity and health conditions each correct response was coded 2 points, “not sure” 1 point, and false erroneous equal 0 points. Next, three metrics were calculated, one for the overall knowledge of health outcomes, KOA; one for the general health and cardiometabolic outcomes, KGH+CM; and one for the reproductive outcomes, KR. Scores were calculated by summing the ratings in the corresponding health conditions of interest, and normalizing the sums from 0 to 1. “0” denoting no knowledge (i.e., all responses were wrong), and “1” denoting all responses were correct. A score of 0.5 could be obtained when all responses were “not sure.”Statistical analysis was conducted with a statistical software package (JMP Pro 12; SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

Descriptive statistics were used for all analysis variables to describe participant characteristics. For categorical variables, frequency counts and percentages were used. Continuous variables were measured using mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Next, correlation analysis was used to identify pair wise associations between age, BMI, correct response rate, and the three knowledge metrics. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to explore predictors of the three knowledge metrics. The exploratory variables were age, BMI, ethnicity group, highest level of education, and total household annual income group. Significance level was set at p<.05.

Results and Discussion

Demographics

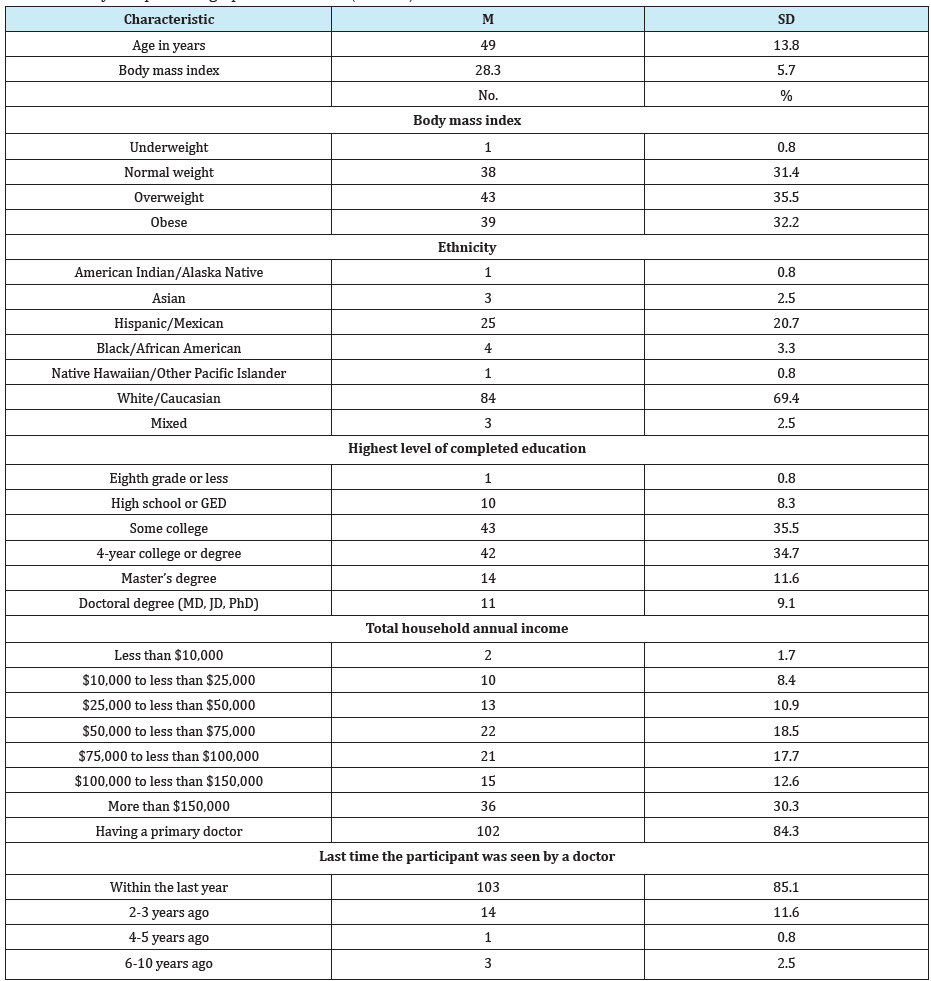

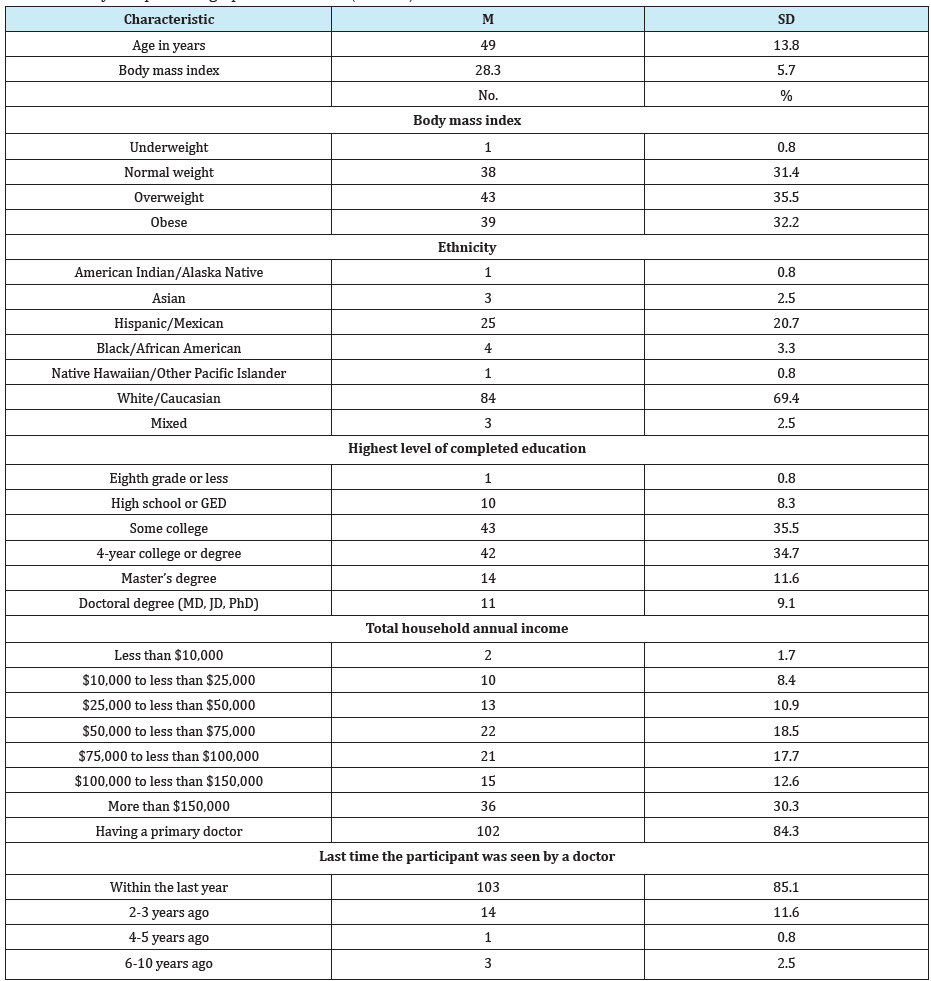

One hundred twenty-one women participated in the study. As shown in Table 1, the average age of the study sample was 49.0±13.8 years, ranging from 23 to 81 years. The average BMI was 28.3±5.73 kg/m2 ranging from 17.3 kg/m2 to 52.1 kg/m2. Based on BMI, 31.4% were classified as having normal weight, and 67.8% had weight above normal. Participants were predominantly white (69.4%), and Hispanic (20.7%). Approximately 90% of the participants had at least some college education, 80% were employed, 94.2% had health insurance, 84.3% had a primary care doctor, approximately 85% had seen a doctor within the last year, over 60% reported a total annual household income per year greater than $75,000.

Table 1: Study Sample Demographic Information (N=121).

Abbreviations: M: mean; SD: standard deviation; No.: Number; GED: general education diploma.

Knowledge of BMI and obesity information

43(35.5%) reported they knew their own BMI, and 78(64.5%) correctly identified the ideal BMI range is 18.5–24.9 kg/m2. Participants were asked about their perception of their current weight: do you consider yourself underweight, normal weight, overweight, or very overweight? Approximately 95% of the normal weight and obese participants correctly characterized themselves. The overall 32.3% misclassification rate was attributed to participants who characterized themselves as overweight (46.7% misclassification rate). Specifically, the 35 participants who identified themselves as overweight were actually either of normal weight (n=21) or obese (n=14). This means approximately 55% of all normal weight participants incorrectly thought of themselves as overweight; approximately 36% of all obese participants incorrectly thought of themselves as being overweight. Forty-three percent of the participants correctly identified that approximately 61% to 80% of the women in the United States weigh more than they should, 2.48% were not sure.

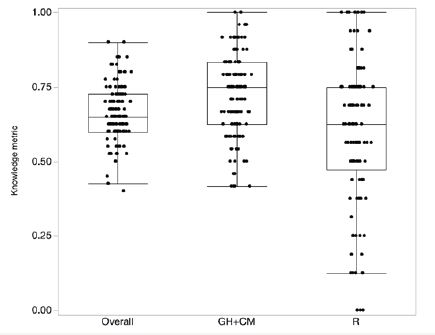

Obesity and health outcomesThe overall correct response rate for all 20 health conditions was only 51.5%, 59.2% for the responses associated general health (GH) and cardiometabolic (CM) outcomes, and 39.9% for the reproductive outcomes. The trend of better knowledge on GH+CM outcomes compared to reproductive outcomes is also evident when we consider the knowledge metrics which include the “not sure” responses. Specifically, the overall metric of participant knowledge on the association between obesity and health outcomes was 0.67±0.10. Participant knowledge on GH+CM outcomes (0.72±0.14) was significantly better than on reproductive outcomes (0.59±0.25, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, S=1553, p<.001). Notably, the correct response rate was increased for the general health and cardiometabolic outcomes in which the correct answer was “yes” (86.8%), but was only 39.6% for the items with “no” being the correct answer.

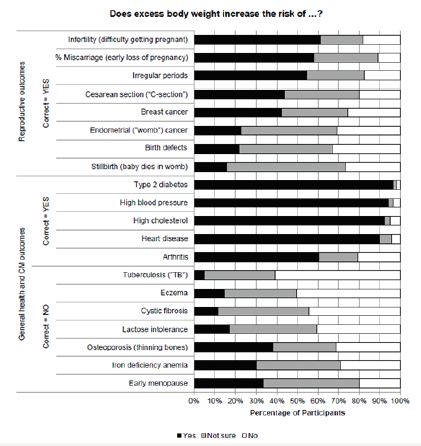

General health and cardiometabolic outcomesFigure 1: Participant responses to the question “Does excess body weight increase the risk of …” grouped by health outcome.“CM” refers to cardiometabolic outcomes.

As shown in Figure 1, most participants correctly identified obesity increases the risk of diabetes (96.7%), high blood pressure (94.2%), high cholesterol (92.6%), heart disease (90.1%), 60.3%, identified the risk of arthritis. In contrast 38% of the participants incorrectly responded that obesity increases the risk of osteoporosis, followed by early menopause (33.1%), iron deficiency anemia (29.8%), lactose intolerance (17.4%), eczema (14.9%), cystic fibrosis (11.2%), and tuberculosis (4.96%). Participants were less confident in their responses when they should correctly answer “no.” Approximately 39% responded they were not sure about the association between obesity and early menopause, iron deficiency anemia, osteoporosis, lactose intolerance, cystic fibrosis, eczema, and tuberculosis.

Reproductive outcomesApproximately 61.2% of the participants correctly identified that obesity increases the risk of infertility. Lower correct response rates were identified for miscarriage (57.9%), irregular periods (54.6%), caesarean section (43.8%), breast cancer (42.8%), endometrial cancer (22.3%), birth defects (21.5%), and stillbirth (15.7%). On average, 22.7% of the respondents noted they were not sure about the association between obesity and reproductive outcomes.

Factors associated with knowledge of the effects of obesityPairwise analysis showed older participants were more aware in their knowledge of general health and cardiometabolic outcomes (Pearson correlation coefficient r=.290, p=.001). The multiple regression model for KOA(R2=.109, F(5,113)=2.76, p=0.022) indicated education level and household income were statistically significant predictors. Specifically, individuals with graduate level education and annual household income of more than $50,000 were more aware of the effects of obesity on health outcomes (Table 2). The multiple regression model for KGH+CM (R2R(R2=.082, F(5,113)=2.03, p=.080) showed individuals with graduate level education were more aware of the effects of obesity on reproductive outcomes.

Table 2: Multiple Regression Models for the Knowledge Metrics.

Abbreviations: b: standardized regression coefficient b; CI: confidence interval. *p<.05

Figure 2: Knowledge metrics. A purposive sample (N=121) of women’s knowledge of cardiometabolic (CM), general (GH), and reproductive (R) risks associated with obesity was examined using The Obesity Health Knowledge Questionnaire (OHKQ). Participants were less knowledgeable about the effect of obesity on R outcomes (39.9%) compared to CM and GH outcomes (59.2%). Improving awareness of obesity risk for R outcomes is essential. The OHKQ integrates questions for assisting nurse practitioners to assess patient knowledge and initiate discussions about obesity health risks. Awareness of and education on potentially serious health related obesity risks may lead to behavior change, decrease health risks, and decrease medical costs.

Figure 2 shows the three knowledge metrics. The lower horizontal line in each box represents the 25th percentile, the upper horizontal line is the 75th percentile. The horizontal line in the box is the median value. The upper end of the vertical line in each box extends to the outermost data point that falls within the distance computed as 75th percentile+1.5*(interquartile range), whereas the lower end of the vertical line extends to the outermost data point that falls within the distance computed as 25th percentile- 1.5*(interquartile range). The interquartile range refers to difference between the 75th and the 25th percentile. If the data points do not reach the computed ranges, then the vertical lines are determined by the upper and lower data point values.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study assessed women’s knowledge of cardiometabolic, general, and reproductive health risks associated with obesity. We found in a sample of educated, financially secure, predominately white women seeking weight management services limited knowledge about the effect of obesity on reproductive health outcomes compared to cardiometabolic and general health outcomes knowledge. Differences are also identified when focusing on the knowledge about general health and cardiometabolic outcomes. Specifically, our participants are clearly aware about diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol, and heart disease. They are less confident about their knowledge about the association of obesity and other aspects of general health.

These findings are supported by previous research conducted by Winston et al. [19] who reported increased knowledge of linkages of obesity with diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol, and heart disease, and the lack of knowledge of the reproductive consequences found by Cardozo et al. [5] and Cardozo et al. [7]. Our results further show our participants’ awareness of the association between obesity and health outcomes was not associated with ethnicity in contrast to previous studies where whites tend to be more knowledgeable on the effects of obesity compared to other ethnic groups [13].

LimitationsThe findings of this study must be considered in context of the study’s limitations. First, the sample is a purposive convenience sample that is relatively homogenous with respect to ethnicity, geographic location, and social economic status, not randomly selected or matched. This nonrandom procedure may influence the findings through self-selection bias. Study participants are already engaged in a weight loss program. Therefore, they may already be more aware of the health risks of obesity compared to the general population. This self-selection bias in the study sample may also bias their responses. Second, the cross-sectional design disallows for changes over time and may not capture the phenomenon under study. Nevertheless the results of this study contribute new knowledge in the assessment of women’s’ knowledge of obesity and risk for health outcomes with a promising brief assessment intended for clinical practice that can be easily implemented in the primary care setting.

Significance for health professionalswith female patients at all ages. Increasing knowledge on aspects of weight and infertility for the young woman desiring pregnancy, and increasing knowledge of risks of stillbirth and cesarean are important to preventing adverse health outcomes. Additionally, recognizing the role of obesity and cancer risks may well motivate women to do what they can to decrease their risks of breast cancer or endometrial cancer. Educational interventions are an important role for all health professionals at the individual and community level. A minute of screening provides valuable patient information. Use of the OHKQ offers a non-threatening approach for assessing risk and initiating targeted discussions with patients addressing obesity implicated health problems.

Statistics and symptomatic patientsThe OHKQ is comprised of questions that PNPs and FNPs could easily integrate into their practices. Its implementation has the potential to initiate a discussion of a routinely avoided topic. The nonprofessional office staff does not need training; the nurse practitioner can choose to address any of the included topics. Followup visits can easily include an evaluation of the patient’s knowledge level by reintroducing the OHRQ and discussing pertinent changes that may or may not have occurred since the prior visit. Use of the OHRQ is one nonthreatening approach for initiating discussions with women while addressing obesity implicated health.

Acknowledgement

The project was supported in part by the University of San Diego Faculty Research Incentive Funds 2016-04-188.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 384(9945): 766-781.

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL (2016) Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 315(21): 2284-2291..

- Arnold M, Jiang L, Stefanick ML, Johnson KC, Lane DS, et al. (2016) Duration of adulthood overweight, obesity, and cancer risk in the Women’s Health Initiative: a longitudinal study from the United States. PLoS Med 13(8): e1002081.

- Beavis AL, Cheema S, Holschneider CH, Duffy EL, Amneus MW (2015) Almost half of women with endometrial cancer or hyperplasia do not know that obesity affects their cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol Rep 13: 71- 75.

- Cardozo ER, Neff LM, Brocks ME, Ekpo GE, Dune TJ, et al. (2012) Infertility patients’ knowledge of the effects of obesity on reproductive health outcomes. Am J Obst Gynecol 207(6): 509.e1-509.e10.

- Okeh NO, Hawkins KC, Butler W, Younis A (2015) Knowledge and Perception of Risks and Complications of Maternal Obesity during Pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale) 5: 323.

- Cardozo ER, Dune TJ, Neff LM, Brocks ME, Ekpo GE, et al. (2013) Knowledge of obesity and its impact on reproductive health outcomes among urban women. J Community Health 38(2): 261-267.

- Norat T, Aune D, Chan D, Romaguera D (2014) Fruits and vegetables: updating the epidemiologic evidence for the WCRF/AICR lifestyle recommendations for cancer prevention. Cancer Treat Res 159: 35-50.

- Song M, Giovannucci E (2016) Preventable incidence and mortality of carcinoma associated with lifestyle factors among white adults in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2(9): 1154-1161.

- Kyrgiou M, Kalliala I, Markozannes G, Gunter M,Paraskevaidis E, et al. (2017) Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites: umbrella review of the literature. BJM 356: j477.

- Soliman PT, Bassett RL, Wilson EB, Boyd-Rogers S, Schmeler KM, et al. (2008) Limited public knowledge of obesity and endometrial cancer risk: what women know. Obstet Gynecol 112(4): 835-842.

- American Dietetic Association, American Society of Nutrition, Siega-Riz AM, King JC (2009) Position of the American Dietetic Association and American Society for Nutrition:obesity, reproduction, and pregnancy outcomes. J Am Diet Assoc 109(5): 918-927.

- Rahman M, Justiss AA, Berenson AB (2012) Racial differences in obesity risk knowledge among low-income reproductive-age women. J Am Coll Nutr 31(6): 397-400.

- Bleich SN, Pickett-Blakely O, Cooper LA (2011) Physician practice patterns of obesity diagnosis and weight-related counseling. Patient Educ Coun 82(1): 123-129.

- Huang T, Borowski LA, Liu B, Galuska DA, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. (2011) Pediatricians’ and family physicians’ weight-related care of children in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 41(1): 24-32.

- Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Stukey HL, Chuang CH, Lehman EB, et al. (2013) A silent response to the obesity epidemic: decline in US physician weight counseling. Med Care 51(2): 186-192.

- Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, Galuska DA, Signore C, et al. (2011) US primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity-, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med 41(1): 33-42.

- Van Leuven K, Prion S. (2007) Health promotion in care directed by nurse practitioners. J Nurs Pract 3(7): 456-461.

- Winston GJ, Caesar-Phillips E, Peterson JC, Wells MT, Martinez J, et al. (2014) Knowledge of the health consequences of obesity among overweight/obese Black and Hispanic adults. Patient Educ Coun 94(1): 123-127.

© 2017 James KS, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)