- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Fecal Calprotectin Test in Clinical Practice

Mahmoud Elkaramany*

Department of Gastroenterology, Hull Royal Infirmary, UK

*Corresponding author: Mahmoud El karamany, Consultant Gastroenterology, Hull Royal Infirmary, 10 Pelhamclose Hu178pn, Hull, England, UK

Submission: December 20, 2017;Published: August 14, 2018

ISSN 2637-7632Volume2 Issue1

Abbreviations:

RAGE: Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products; IBD: Inflammatory Bowel Disease; IBS: Irritable Bowel Syndrome; DAMP: Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern

Mini Review

Calprotectin is a protein derived from leukocytes that appears in the intestinal mucosa when there is inflammation. It belongs to the family of low molecular weight proteins S100 and is found in large quantities in the granules of neutrophils where it forms 60% of cytoplasmic proteins. It is a polypeptide formed of one light chain and two heavy chains with a molecular weight of 36.5kDa [1,2]. This protein has antimicrobial and bacteriostatic functions and is attributed an active role in the body’s defenses.S100A8 (calgranulin A) and its binding partner S100A9 (calgranulin B) exhibit increased levels in several inflammatory states. Calgranulin A and calgranulin B form the heterocomplex S200A8/9, more commonly known as calprotectin. The effects of calprotectin are mediated by calcium flux after activation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Calprotectin is released from damaged cells through an atypical pathway that requires protein kinase C and RAGE, thus making calprotectin a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule [3].

When an inflammatory process is carried out in the intestine, neutrophils are attracted to the inflammatory site where they degranulate and secrete calprotectin, which due to its high affinity to calcium, remains stable and resistant to enzymatic degradation for a period of approximately 7 days at room temperature [4]. Being resistant to degradation by enzymes and bacteria, it travels through the intestine along with its contents and is secreted in the stool. This makes fecal calprotectin a simple, non-invasive and easy-toanalyze biomarker that assesses inflammatory bowel activity in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis [5].The use of fecal calprotectin has been studied for more than a decade, and its use to differentiate between Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) has been proven. In Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, it has been shown to predict the rate of relapse [5].

The nonspecific clinical manifestations of gastrointestinal inflammatory diseases make it necessary to use tools such as colonoscopy and histology to reach the diagnosis, however, these methods are expensive and invasive. Studies have shown high levels of fecal calprotectin in patients with IBD, compared to healthy controls and patients with IBS. In this way, fecal calprotectin also becomes useful to differentiate between IBD and IBS [6]. Intestinal inflammatory diseases are of unknown etiology, in which mucosal healing is the therapeutic objective [7]. The most appropriate biomarker to assess the activity or remission of the disease is fecal calprotectin. Low levels of fecal calprotectin have been observed after pharmacological treatment, which correlates with the healing of the intestinal mucosa [8].

The maximum limit of fecal calprotectin in healthy individuals is 50μg/g with a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 91%. There are other studies in which values of 24-150μg/g proves to be normal in patients with inflammatory bowel disease with a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 96%. For colon cancer, fecal calprotectin turns out to be an unreliable biomarker with 31% sensitivity and 71% specificity [8]. It is well known that chronic inflammation is a risk factor for gastrointestinal malignancy. Patients suffering from IBD have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer. Fecal calprotectin seems to be a marker with more sensitivity for gastrointestinal cancer than the fecal occult blood test, however, it does not have the specificity necessary to be part of routine laboratory tests in populations with risk factors. Of all the fecal inflammatory markers, calprotectin appears to be the most promising, due to the fact that this protein is elevated in subjects with inflammatory bowel disease and correlates with histological findings of inflammation [9].

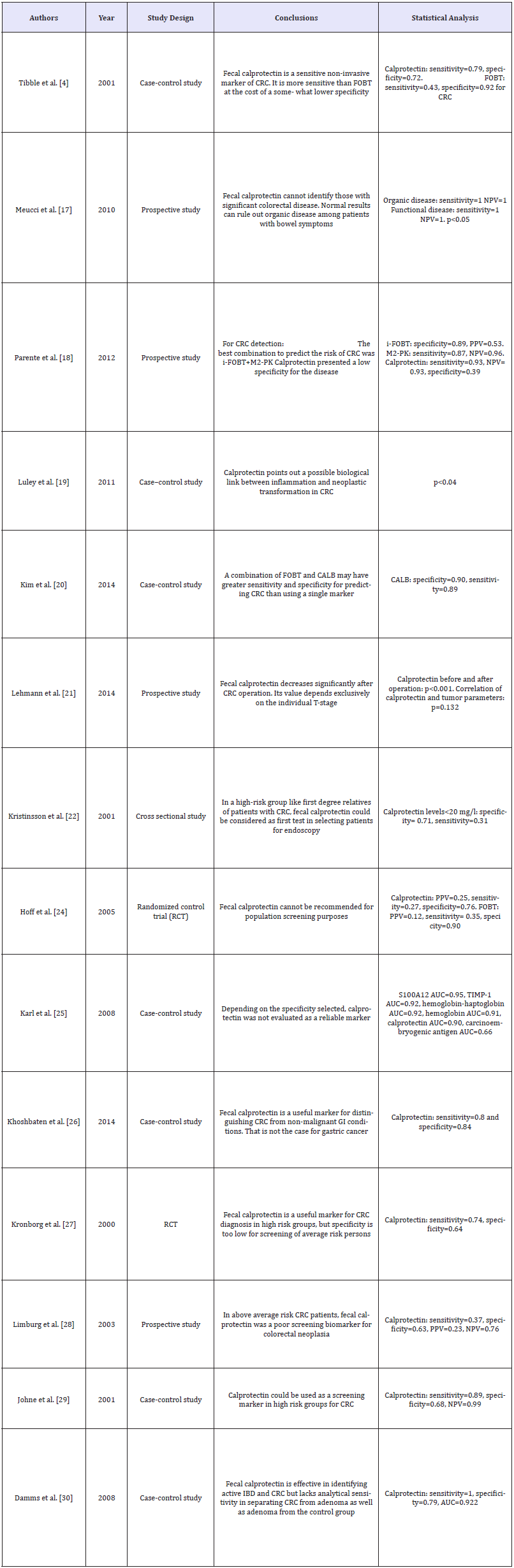

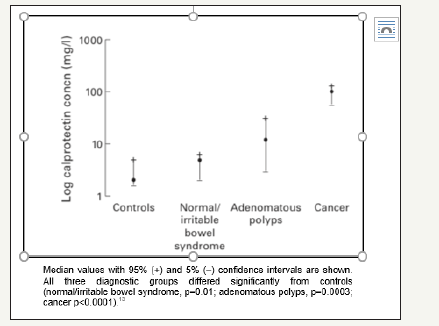

Meta-analyzes have been carried out to evaluate the use of fecal calprotectin in colorectal cancer comparing histological findings with fecal calprotectin levels in which a relationship betweenelevated calprotectin levels and histological malignancy has not yet been confirmed [10]. Other studieshave evaluated the role of calprotectin in colorectal cancer resulting in diverse conclusions [3] (Table 1).The British Journal of General Practice suggests there are enough inflammatory components in patients with colorectal cancer to provide high levels of fecal calprotectin [11], which is supported by other studies that indicate fecal calprotectin decreases significantly after colorectal cancer operation [12]. Tibble et al. [12] studied fecal calprotectin concentrations in healthy controls, IBS, adenomatous polyps and cancer, resulting in elevated levels of this biomarker in all three diagnostic groups, cancer being the most significant (p< 0.0001) [13] (Figure 1). Most colorectal cancer patients have elevated levels of fecal calprotectin and research shows its value depends exclusively on the T-stage. Patients with T3 and T4 tumors tend to have significantly higher fecal calprotectin levels than those with T1 and T2 stages [12].

Table 1:

Figure 1:Log fecal calprotectin concentration (mg/l) in the different diagnostic groups [13].

Even though additional studies are needed to determine the specific cutoff levels of calprotectin associated with colonic pathology, it is proven that the combination of fecal occult blood tests and fecal calprotectin tests together improve the sensitivity and specificity for detection of colorectal cancer and adenoma, compared to each of the tests individually. The measurement of both markers could be effective in excluding causes of gastrointestinal bleeding unrelated to an inflammatory process [10,14]. Fecal calprotectin is a new biomarker that has not been thoroughly studied but seems to be a sensitive, reliable tool in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer [15], at the expense of having very little specificity and no proven correlation to the stage of the disease.

References

- Sergio B (2004) Fecal calprotectin. Applications in gastroenterology. Villavicencio foundation 12: 87-88.

- Edouard L (2015) Fecal calprotectin: towards a standardized use for inflammatory bowel disease management in routine practice. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 9(1): 1-3.

- Moris D, Spartalis E, Angelou A, Margonis GA, Papalambros A (2016) The value of calprotectin S100A8/A9 complex as a biomarker in colorectal cancer: A systematic review. J BUON 21(4): 859-866.

- Gompertz G, Macarena (2012) Role of inflammation and measurement of fecal calprotectin in irritable colon syndrome. Rev Hosp Clín Univ Chile 23: 335-339.

- Anders L (2014) Gothenburg University Publications Electronic Archive. University of Gothenburg.

- Mowat C Digby, Strachan JA, Wilson R, Carey FA, Fraser CG, et al. (2016) Faecal haemoglobin and faecal calprotectin as indicators of bowel disease in patients presenting to primary care with bowel symptoms. Gut 65(9): 1463-1469.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013) Faecal calprotectin diagnostic tests for inflammatory diseases of the bowel. p. 1-56.

- Kennedy NA, Clark A, Walkden A, Chang JC, Fascí-Spurio F, et al. (2014) Clinical utility and diagnostic accuracy of faecal calprotectin for IBD at first presentation to gastroenterology services in adults aged 16–50 years. J Crohns Colitis 9(1): 41-49.

- (1996) United Healthcare Oxford. Fecal calprotectin testing, p. 1-9.

- Widlak MM, Thomas CL, Thomas MG, Tomkins C, Smith S, et al. (2017) Diagnostic accuracy of faecal biomarkers in detecting colorectal cancer and adenoma in symptomatic patients. Aliment pharmacol ther 45(2): 354-363.

- (2016) Faecal calprotectin in patients with suspected colorectal cancer: a diagnostic accuracy study. Br J Gen Pract pp. 499-506.

- Frank Serge Lehmann, Francesca Trapani, Ida Fueglistaler, Luigi Maria Terracciano, Markus von Flüe, et al. (2014) Clinical and histopathological correlations of fecal calprotectin release in colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 20(17): 4994-4999.

- Tibble J, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Sherwood R, Fagerhol M (2001) Faecal calprotectin and faecal occult blood tests in the diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma and adenoma. Gut 2001(49): 402-408.

- Poullis A, Foster R, Shetty A, Fagerhol MK, Mendall MA, et al. (2004) Bowel inflammation as measured by fecal calprotectin: a link between lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk. American association for cancer research 13(2): 279-284.

- Ariella Bar Gil Shitrit, Dan Braverman, Halina Stankiewics, David Shitrit, Nir Peled (2007) Fecal calprotectin as a predictor of abnormal colonic histology. Dis Colon Rectum, p. 1-6.

© 2018 Mahmoud Elkaramany. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)