- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Celiac Disease and "Idiopathic" Portal Hypertension: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Khaled Matar1*, Rami Musallam2 and Manik Sharma3

1*European Gaza Hospital, Palestine

2*European Gaza Hospital, Palestine

3*Hamad Medical Corporation, Qata

*Corresponding author: Khaled Matar MD, European Gaza Hospital, Khanyounis City-Alfukhari, Gaza Strip-Palestine

Submission: August 24, 2017; Published: December 15, 2017

ISSN 2637-7632

Volume1 Issue1

Abstract

Idiopathic Portal hypertension (IPH) is a disorder of unknown etiology. We are reporting a case of IPH and Celiac disease. A 39-year old female patient was referred to gastroenterology clinic for diagnostic work-up of severe pancytopenia, massive splenomegaly and tense ascites. Diagnosis of IPH was clinically suspected after exclusion of possible causes that can manifest as portal hypertension. Endoscopy revealed esophageal varices along with atrophic folds and scalloping in the second part of the duodenum. Celiac disease was diagnosed based on histopathology findings and strong serology positivity for anti- tissue transglutaminase IgA. Her symptoms improved on a gluten-free diet and laboratory tests results improved considerably with significant reduction of the spleen size and ascites.

Conclusion: We suggest that physicians should be aware of this unusual association between celiac disease and IPH. Early diagnosis and proper treatment of Celiac disease not only helps to obviate the need for further unwarranted invasive procedures but also helped in improvement of portal hypertension.

Introduction

Idiopathic Portal hypertension (IPH) is a disorder of unknown etiology. It manifest as splenomegaly, pancytopenia, esophageal varices and ascites [1]. The disease is diagnosed by the presence of unequivocal evidence of portal hypertension in the definite absence of liver cirrhosis and extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) [2].

We are reporting a case that presented with severe form of portal hypertension with hypersplenism that significantly improved after initiation of gluten-free diet.

Case Presentation

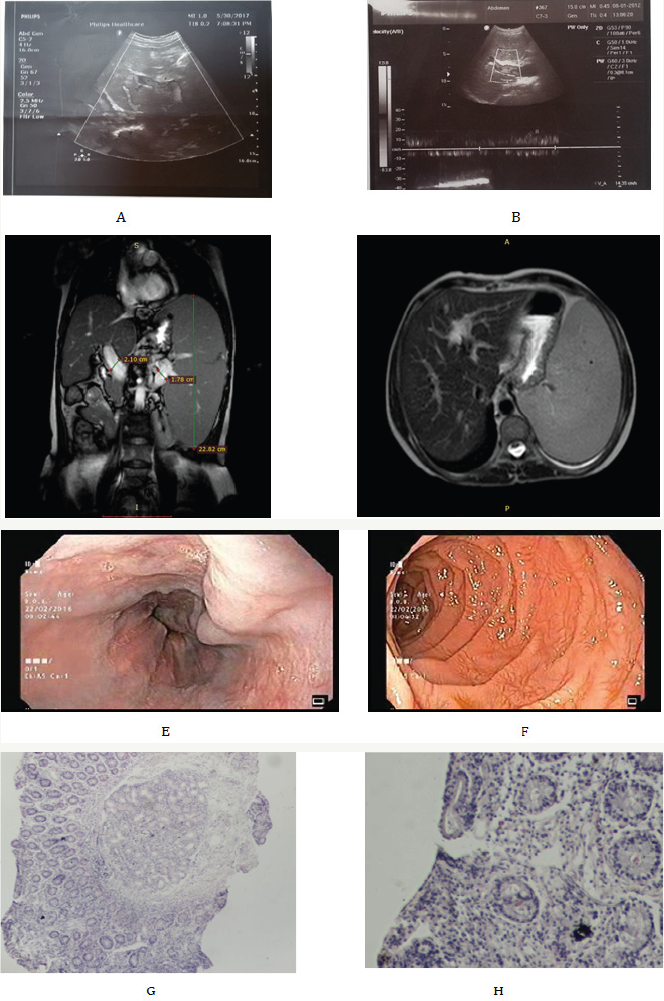

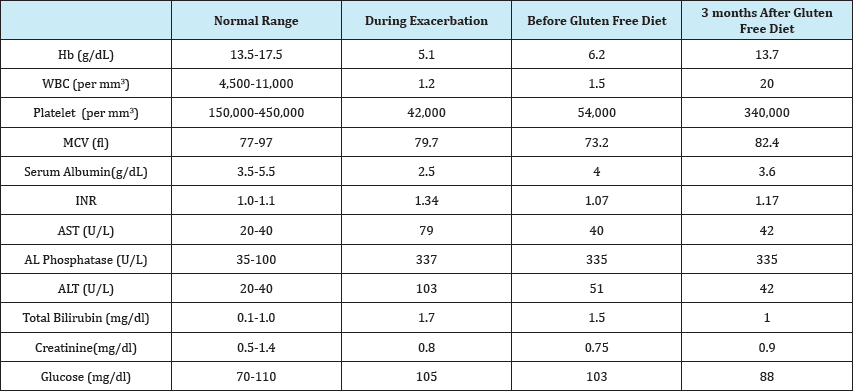

A 39-year old female patient was referred to gastroenterology clinic from hematology department for diagnostic work-up for her pancytopenia, splenomegaly and ascites. The patient complained of fatigue, weakness and early satiety. On physical examination, she appeared pale. Her abdomen was distended with shifting dullness and a massive splenomegaly. Her lab tests showed pancytopenia, normal albumin, normal Internationalized Normalization Ratio (INR), normal total bilirubin and mild elevation of ALT, AST and Alkaline phosphatase (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasound revealed normal sized liver, homogenous in echogenicity without focal lesion. Spleen was enlarged up to 21cm without focal lesion. Doppler ultrasound revealed dilated portal vein (up to 18mm) without thrombosis, intact hepatic veins and dilated splenic vein (Figure 1A & 1B). A contrast enhanced MRI of the abdomen revealed normal size, shape and intensity of liver with enlarged spleen (22.3cm), dilated splenic vein (1.8cm) and portal vein (1.7cm) with multiple collaterals at the splenic hilum (Figure 1C & 1D). Hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C antibody, autoimmune markers including Anti- nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) and anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) were negative. None of the laboratory findings indicated hemochromatosis. Peritoneal fluid examination revealed high SAAG ascites.

During follow up, liver biopsy was planned after correcting coagulopathy. Meanwhile, endoscopy revealed Grade I-II esophageal varices along with atrophic folds and scalloping in the second part of the duodenum. D2 biopsy revealed marked villous atrophy along with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes. (Figure 1G & 1H). Serology studies revealed positive anti- tissue transglutaminase (tTG IgA) and anti endomysial antibody (EMA IgA).

A gluten free diet was initiated. Follow up visit after 3 months showed significant improvement in hemoglobin, platelet count, and white blood cells and liver function test. There was a significant reduction of the spleen size confirmed by ultrasound (Table 1).

Figure 1: US Doppler view of the patent portal vein and right hepatic vein (A,B) MRI abdomen revealing normal size, shape and single intensity of liver with enlarged spleen(C, D) Gastroscopy revealing esophageal varices (E) and scalloped D2 folds (F) and Microscopic examination of duodenal mucosa showing blunt villous architecture and increase intraepithelial lymphocytes (G, H).

Table 1: Biochemical values at presentation and post treatment with Gluten Free diet.

Discussion

Celiac disease (CD) is a systemic immune-mediated disorder triggered by dietary gluten in genetically susceptible persons. Gluten is a protein complex found in wheat, rye, and barley. Celiac disease occurs in nearly 1% of the population in many countries. The diagnosis is usually established on the basis of symptoms, serologic testing, duodenal biopsy and response to a gluten-free diet[3].

Patients with Celiac disease may present with classical clinical manifestations of weight loss, anemia, diarrhea, and general weakness. Rarely, it may present with metabolic bone disease, iron, or folate deficiencies (osteoporosis, fractures, or anemia), neurologic symptoms (ataxia, encephalopathy, or myelopathy) or associated autoimmune diseases that are often of greater clinical significance than celiac disease [4].

There are more than seven review articles which have discussed liver involvement in patients with celiac disease by various authors Narciso S et al. [5], Anania et al. [6], Rostami N et al. [7], Zali et al. [8], Freeman [9], Prasad et al. [10] and Rubio T et al. [11]. Narciso S et al. [5] recommended active screening for celiac disease in patients with liver diseases, particularly in those with autoimmune disorders, steatosis in the absence of metabolic syndrome, non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension, and cryptogenic cirrhosis planning for liver transplantation [5]. Rostami N et al. [7] also concluded that there are stronger links between CD and autoimmune liver disorders. CD seems to be contributing to portal hypertension where no liver disease is evident. Zali et al. [8] concluded that serological evaluations for CD should be part of the general workup of patients with unexplained elevated liver enzyme levels when other causes of liver disease have been ruled out. In another review, it was found that 4%-13% of patients with Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), 3-7% of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, 3-6% with autoimmune hepatitis and 2-3% with primary sclerosing cholangitis are affected by celiac disease [10]. According to Rubio T et al. [11] Isolated hypertransaminasemia, with mild or nonspecific histologic changes in the liver biopsy, also known as "celiac hepatitis", is the most frequent presentation of liver injury in celiac disease. Volta et al. [12] also concluded that there is close association between celiac disease and autoimmune liver disorders.

Mild liver dysfunction is often reversed by gluten free diet (GFD), but Kaukinen et al. [13] showed that GFD may even prevent progression of liver disease. He recommended that presence of celiac disease should be investigated in all patients with severe liver disease awaiting transplantation.

The relation between idiopathic portal hypertension and celiac disease has been reported in few case reports only. This case and other reported cases suggest the relationship between idiopathic portal hypertension and celiac disease. This case also highlights improvement of portal hypertension by gluten-free diet and thereby obviating the need for further unwarranted invasive procedures including liver biopsy. Timely detection and effective treatment of celiac disease can go a long way in management of portal hypertension especially in resource poor countries.

References

- Okudaira M, Ohbu M, Okuda K (2002) Idiopathic portal hypertension and its pathology. Semin Liver Dis 22(1): 59-72.

- Dhiman RK, Chawla Y, Vasishta RK, Kakkar N, Dilawari JB, et al. (2002) Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (idiopathic portal hypertension): experience with 151 patients and a review of the literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 17(1): 6-16.

- Green PH, Cellier C (2007) Celiac disease. N Engl J Med 357(17): 17311743.

- Green PH, Jabri B (2003) Coeliac disease. Lancet 362(9381): 383-391.

- Narciso-SJL, Schiavon LL (2017) To screen or not to screen? Celiac antibodies in liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol 23(5): 776-791.

- Anania C, De Luca E, De Castro G, Chiesa C, Pacifico L (2015) Liver involvement in pediatric celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol 21(19): 5813-5822.

- Rostami-NM, Haldane T, Aldulaimi D, Alavian SM, Zali MR, et al. (2013) The role of celiac disease in severity of liver disorders and effect of a gluten free diet on diseases improvement. Hepat Mon 13(10).

- Zali MR, Rostami NM, Rostami K, Alavian SM (2011) Liver complications in celiac disease. Hepat Mon 11(5): 333-341.

- Freeman HJ (2010) Hepatic manifestations of celiac disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 3: 33-39.

- Prasad KK, Debi U, Sinha SK, Nain CK, Singh K (2011) Hepatobiliary disorders in celiac disease: anupdate. Int J Hepatol 2011: 438184.

- Rubio TA, Murray JA (2008) Liver involvement in celiac disease. Minerva Med 99(6): 595-604.

- Volta U, Murray JA (2008) Liver dysfunction in celiac disease. Minerva Med 99(6): 619-629.

- Kaukinen K, Halme L, Collin P, Farkkila M, Maki M, et al. (2002) Celiac disease in patients with severe liver disease: gluten-free diet may reverse hepatic failure. Gastroenterology 122(4): 881-888.

© 2017 Khaled Matar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)