- Submissions

Full Text

Global Journal of Endocrinological Metabolism

Metabolic Control in Patients with Type1 Diabetes Attending a Residential Diabetes Camp in Mauritius

Pravesh Kumar Guness*

Department of Medicine/Psychosocial, T1Diams NGO, Quatre Bornes, Mauritius

*Corresponding author: Pravesh Kumar Guness, Department of Medicine/Psychosocial, T1Diams NGO, Quatre Bornes, Mauritius

Submission: April 04, 2018;Published: April 11, 2018

ISSN: 2637-8019Volume1 Issue5

Abstract

Introduction: Diabetic camps have become an integral part in the life of people with Type1 diabetes. The aim of this study is to prospectively evaluate the impact of a winter camp on the metabolic control of patients with Type 1 diabetes.

Methods: In Mauritius Island, a seven-day residential camp was organised by non-governmental organisation, T1Diams, in 2014 for 27 diabetic members aged above 12 years. Blood glucose levels were compiled on Microsoft Excel® and analysed on IBM Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) ®. The relationship of sex, age, Body Mass Index (BMI), duration of diabetes, ratio of total dose of insulin per day to weight (iU/kg) and insulin regimen on hypoglycaemia (blood glucose<3.3mmol/l) and hyperglycaemia (blood glucose>11.1mmol/l) frequency were determined. The managing committee of the organisation gave the approval to carry out this study.

Results: Two patients left the camp on the eve of departure. 339 blood glucose readings were reported. The average total dose of insulin per day for each patient was 49.9+13.4(iU). Mean blood glucose levels were 8.23mmol/L before breakfast, 8.32mmol/l before lunch, 7.89mmol/l before dinner and 13.0mmol/L at bedtime. Pre-prandial mean blood glucose decreased by 33.3% before breakfast and 20.9% before dinner by the last day of camp relative to the first day. Two cases of severe hypoglycaemia were noted requiring administration of intravenous 30% glucose solution. No case of ketoacidosis was reported. 18 (5.3%) cases of hypoglycaemia and 134 (39.5%) readings were above 11.1mmol/L. There was a negligible increase of 0.25 + 1.35 % (p> 0.05) of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) after the camp. The relationship between frequency of hypoglycaemia and sex was statistically significant (p<0.05) and for the other variables no relationship was found (p>0.05).The frequency of hyperglycaemia was not associated with sex, age, BMI, duration of diagnosis, ratio of total dose of insulin per day to weight and insulin regimen (p>0.05).

Conclusion: It is the first time that this study has been carried out in Mauritius. Attending T1Diams winter residential diabetic camp is associated with improved glycaemic control and stabilisation of HbA1c. Our study showed that frequency of hypoglycaemia depends on sex whereas frequency of comparison among T1Diams camps. In any case, present day camping experiences are essential.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes; Diabetic camp; T1Diams; Mauritius Island; Therapeutic education; Nongovernmental organisation; Winter diabetic camp management; Hypoglycaemia; Hyperglycemias

Introduction

Paediatric and adolescent Type 1 diabetes is the third most common chronic pathology in this age group [1]. Type1 diabetes encompasses behavioural changes in nutrition, physical activity and daily dose of insulin. It is also associated with multiple daily injections or use of insulin pump and continuous glucose monitoring. There is no other chronic disease that is so reliant upon what the patient does incessantly every minute, hour by hour, than Type 1 diabetes [2]. So, patients with Type 1 diabetes must try to accept the responsibility of self-care by acquiring self-management skills and make life style changes so that the intensive management can delay or slow the progression of micro and macro vascular complications [3,4].

Diabetic Therapeutic Patient Education (TPE) is intended to empower patients with the skills and knowledge of self-managing or adapting treatment to their particular chronic disease and in coping processes and skills. The patients, being autonomous in managing their condition, will reduce avoidable complications, while having a good quality of life. Furthermore, this reduces the cost of long-term care of Type 1diabetes to society [5]. In nearly all clinical settings, any patient diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes will receive initially an intensive education on diabetes management and will be reviewed in outpatient departments regularly. However patients’ ways of life, learning ability, social behavior and the characteristics of the disease, all change as the patient grows older, so appropriate personalised education is essential [6].

In Mauritius Island, T1 Diams (Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Support), a Mauritian non-profit organisation is specialised in the care and self-management of Type 1 diabetics on the island. They have been working on the development and implementation of diabetic therapeutic education for the last ten years. It achieves its goals by using diabetes related games during home visits of members, organising regularly diabetic recreation days and holding an annual winter diabetic camp. Since 2005, the yearly diabetic camp provides an opportunity to consolidate knowledge on diabetes, to improve quality of life, to improve the psychological well-being, to acquire self-esteem and self-confidence among their members [7]. There are numerous studies that have shown the positive effect of knowledge and self-management of the disease [8,9]. Therefore the aim of this study is to evaluate prospectively, among patients with Type 1 diabetes, the impact of a winter camp on their metabolic control (HbA1c and blood glucose levels).

Research Design and Methods

Study type

We did a cross-sectional study that included 27 adolescents and young adults aged between 13 and 22 with Type 1 diabetes, attending a 7-day summer camp in Mauritius in August 2014. The winter camp was organised by T1Diams and funded by donations.

There was a medical team (one doctor, one nurse and one diabetes educator) present for the whole duration of the camp. Prior to the camp a standardised chart including information on the patients’ medical history, diabetes regimen, previous glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level and medication, was filled in by telephone conversation. On the first day of the camp, the patients were required to report the insulin dosages and blood glucose values during two days prior to the camp. A portable standiometer and a properly calibrated scale were used to measure heights and weights respectively.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the online calculator for BMI-for-age percentile on a CDC BMI-for-age growth chart [10]. A minimum of four blood glucose measurements was measured per day (one measurement before each meal [breakfast, lunch and dinner] and one at bedtime (10 pm) for all participants, using the Accu-Chek Freestyle® glucometer. However the measurement was repeated when hypoglycaemia was suspected clinically. The blood glucose levels data stored in the glucometers were transferred to a computer using the Roche Diagnostics Accu-Chek Smart Pix® device. For each participant, the Roche Diagnostics Accu-Chek Smart Pix® Data Management System software automatically calculated the percentage of blood glucose values for hypoglycaemia (glycaemia<3.3mmol/l]), normoglycaemia (glycaemia 4.4-6.6mmol/l]) and hyperglycaemia (glycaemia≥6.6mmol/l]). Severe hypoglycaemia was defined as one requiring intramuscular injection of Glucagon or intravenous 30% Glucose solution.

Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level was done for every patient by capillary blood sample using the DCA Vantage® Analyzer which meets the technical standards of the National Laboratory of Mauritius of the Ministry of Health and Quality of Life. The Hb1Ac levels were done on the first day of camp and 3 months post camp. Diabetes therapeutic education was carried out in the morning session (10 am to 11.30 am). The education programme included brief overview of the human body, what is Type 1 diabetes, recognition and management of hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia and ketosis, insulin injection techniques, blood glucose monitoring, insulin dosage adjustment based on food intake and activity, carbohydrate counting and complications of diabetes. Moreover during the camp, group discussions are encouraged so that the patients relate to their peers regarding their personal experience on the management of Type1 diabetes. The afternoon session consisted mainly of physical activities such as swimming, indoor games, football, dancing and various fun games.

Insulin regimen

The insulin therapy regimens of the patients were left unchanged for the first 24 hours of the camp. Every injection on the camp was supervised by the nurse specialised in diabetes. Only one patient was on two injections per day (premixed insulin) and all the others were on four times injections per day (three pre-prandial rapid acting insulin and one long acting insulin at bedtime). If there was no obvious cause found for observed hypoglycaemia or hyperglycemia, the dose of insulin for the next day was adjusted accordingly.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the managing committee of the organisation for the study. All the participants gave verbal consent to participate in the study and their parents signed an informed consent form.

Data processing and analysis

Data entry, interpretation and statistical analysis were done and analysed on IBM SPSS®. Microsoft Excel® (Office 2007) was used to create the tables and charts. P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

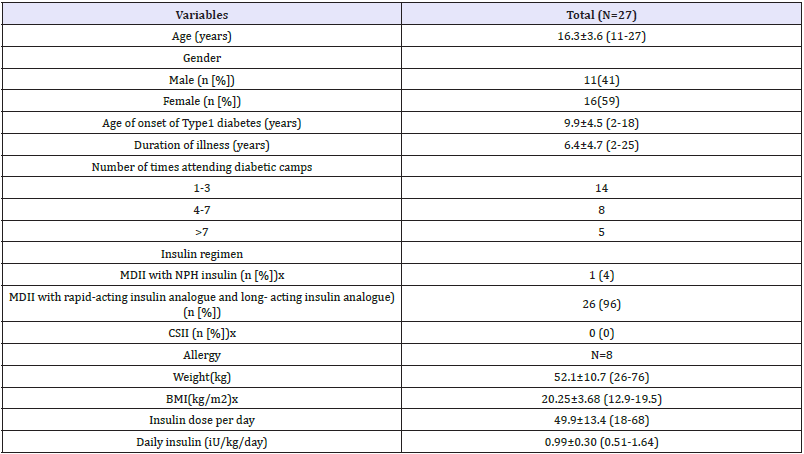

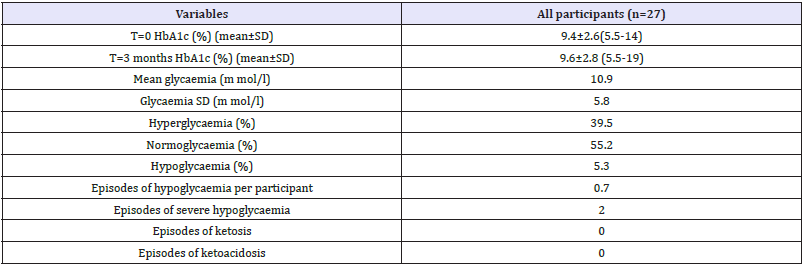

27 patients (11 males and 16 females), aged above 12 years, attended the camp but 2 (one male and one female) left the camp on the eve prior to departure (for family reasons) (Table 1).

Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI-for-age percentile on a CDC BMI-for-age growth chart showed that 18.5% (n=5) was underweight, 14.8 % (n=4) overweight and 66.7 % (n=18) had normal weight.

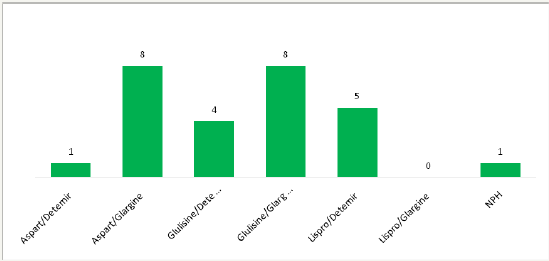

Insulin

The ratio of total insulin per day to weight was calculated. It was found that the mean of this value was 0.99±0.3iU/kg/day. Two patients had an inverse ratio of rapid insulin analogue to slow insulin analogue. The ratio of rapid acting insulin analogue to long acting analogue was 1.55±0.66. The hypoglycaemic effect of rapid acting analogue was calculated using the formula: 1 unit of rapid acting analogue=100/ (total dose of insulin/day). This value was 2.2±0.88mmol/l. Figure 1 shows number of patients on different insulin regimen.

Table 1: Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise specified.

BMI: Body Mass Index; CSII: Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion; MDII: Multiple Daily Insulin Injections; NPH: Neutral Protamine Hagedorn

Figure 1: Frequency of patients on different types of insulin.

Glycaemia control

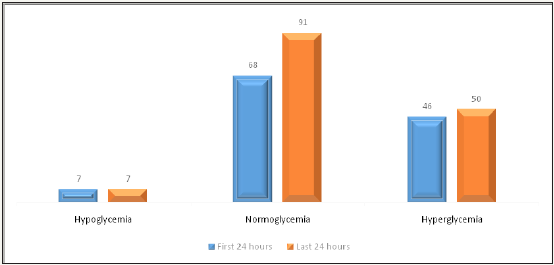

There was a total of 339 blood glucose level (BGL) data reported and analysed. The mean BGL per patient on the first day of the camp were 8.23mmol/L before breakfast, 8.32mmol/l before lunch, 7.89mmol/l before dinner and 13.0mmol/l at bedtime. On the last day of the camp there was a significant reduction in the mean pre-prandial blood glucose of 33.3% (breakfast) and 20.9 % (dinner). There was an increase by 7.9% and 36.7% pre-prandial blood glucose for lunch and bed-time (22h00) respectively. Figure 2 shows the number of hyper, normo and hypo-glycaemia for the firstand last 24 hours of the camp. There was a 33.8% increase in the percentage of normoglycaemia at the end of the camp. There was a stabilisation of the frequency of hypoglycaemia (n=7, N=7) and hyperglycaemia (n=46, N=50) on the first and last day.

Figure 2: Frequency of patient’s v/s glycemia during the first 24 hours and last 24 hours of the winter diabetic camp.

Metabolic control

The mean number of episodes of hypoglycaemia per patient during the camp was 0.7. Two children had an episode of severe hypoglycaemia requiring intravenous injection of 30% glucose to resolve it. 134 readings showed hyperglycemia (>11.1mmol/l)). No case of ketosis or keto-acidosis was reported (Table 2). On the first day, 15% had an HbA1c value ≤7.5% (58mmol/mol). We also noticed that when we measured the HbA1c levels at three months post camp, there was an increase of 0.25+1.35%. (-4.2, +4.4) (p>0.05).

Table 2: Markers of glycaemic control and glycaemic variability for the whole duration of camp.

SD: Standard Deviation; HbA1c: Haemoglobin A1C; hypoglycaemia (glycaemia<3.3mmol/l), normoglycaemia (glycaemia between 3.3 and 11.1mmol/l) and hyperglycaemia (glycaemia>11.1mmol/l

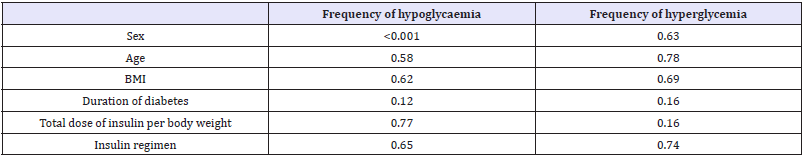

The correlation between blood glucose and several variables is shown in Table 3. During the camp no correlation was found between frequency of hypo or hyper glycaemia with age, BMI, duration of diagnosis, ratio total dose of insulin per day to weight and insulin regimen. However, there was a direct correlation between frequency of hypoglycaemia and sex (P<0.05, Pearson R correlation).

Discussion

The idea of having residential diabetic camps for children and adolescents with Type 1 diabetes has become widespread worldwide [2]. The organization of camps is an enormous project that requires well established protocols and a close co-operation between the organising committee and camp medical staff. T1Diams has been using the guidelines from the association Aides aux Jeunes Diabétiques (AJD) [11] of France which itself derived from the latest International Society for Paediatrics and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) guidelines [12]. The duration of camp depends mainly on the financial resources of camp and campers. It may vary from a seven day camp to four weeks [2]. For the last eight years, it has been of one week’s duration in Mauritius.

Table 3: P-values for Pearson’s R correlation tests between frequency of hypoglycaemia/ hyperglycaemia and camper characteristics.

There are many factors that are responsible to improve blood glucose levels such as diabetes therapeutic education, frequent physical activities, pre-planned meals and a structured setting with supervised insulin injections and regular testing of blood glucose levels [13]. Those camps provide an opportunity to study blood glucose levels outside the hospital setting [14]. So we are presenting the first-ever study, to our knowledge, on blood glucose levels in a Mauritian residential diabetes camp. The range, mean and standard deviation of the blood glucose levels were better compared to others which reported means ranging from 9.5 to 11.0mmol/L [15].

Some studies reported 0.1 to 0.7 episodes of hypoglycaemia per camper per day [15,16]. On the first day of the camp, there were seven cases of hypoglycaemia. Normally, it has been found that hypoglycaemic episodes are common on the first day because the carbohydrate intake and physical activities differs from the patient daily routine [17]. Our study similarly showed that the mean number of episodes of hypoglycaemia per patient during the camp was 0.7.

There were two episodes of severe hypoglycaemia on the camp requiring injection of intravenous 30% glucose solution. Similarly it was reported in a seven-day camp in Arizona that out of the 28 episodes of severe hypoglycaemia, one required intravenous glucose infusion [18]. Furthermore Gandrud et al. [19] had two cases of severe hypoglycaemia out of their 45 campers.

Moreover, at the end of the camp there was a considerable increase (33.8%) (all measured) of normoglycaemia. Carlson et al. [20] showed that in 2009 and 2010, there was 45% and 50% of patients who reached normal blood glucose levels. There was no significant change in glycosylated haemoglobin 0.25 + 1.35 % (p>0.05) after the camp. Other studies have shown that attending a diabetic camp resulted in a significant decrease in HbA1C levels post camp [21]. There is a strong relationship between the frequency of hypoglycaemia and gender (female) (p<0.05). Lekie et al. [22] showed that the frequency of hypoglycaemia is more in women compared to male.

Conclusion

It is the first time that this study has been carried out in Mauritius. Attending T1 Diams winter diabetic camp is associated with improved glycaemic control and stabilisation of Hba1C. Our study showed that frequency of hypoglycaemia depends on gender whereas frequency of hyperglycaemia was independent of the variables studied. The benchmark has been established for future comparison among T1 Diams camps. In any case nowadays camping experiences are essential for young Type1 diabetics.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are made regarding the management of Type1 diabetes on residential camps:

i. Due to the beneficial effect on blood glucose levels, patients with Type1 diabetes should be encouraged to attend annual residential camps.

ii. The camp provides real-life situation to assess the knowledge and skills of young diabetics to manage their blood sugar level.

iii. In developing countries, the camp provides an ideal setup to collect research data on blood sugar management of young diabetics.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Mr Didier Jean Pierre, Mr Abdullah Dustagheer, Mrs Bianca Labonté, Dr Baptiste Valle, the working staff of T1Diams and Dr Zahrah Atchia for their help and general support for this article.

References

- Dantzer C, Swendsen J, Maurice Tison S, Salamon R (2003) Anxiety and depression in juvenile diabetes: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev 23(6): 87-800.

- Brink JS (1996) Diabetes camping and youth support programs. In: Lifshitz F (Ed.), Pediatric endocrinology, (3rd edn), Marcel Dekker, New York, USA, pp. 671-676.

- Linda Hass, Melinnda Maryniuk, Joni Beck et al. (2012) National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Care 35(11): 2393-2401.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1993) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329: 977-986.

- World Health Organization (1998) Therapeutic Patient Education.

- Menising C, Boucher J, Cypress M (2006) National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care 29(Suppl 1): S78-S85.

- Guness PK, T1 Diams (2017) Type 1 diabetic camp: An experience in Mauritius. J Soc Health Diabetes 5(2): 66-70.

- Mancuso M, Caruso Nicoletti M (2003) Summer camps and quality of life in children and adolescents with Type1 diabetes. Acta Biomed 74(Suppl 1): 35-37.

- Misuraca A, Di Gennaro M, Lioniello M, Duval M, Aloi G (1996) Summer camps for diabetic children: an experience in Campania, Italy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 32(1-2): 91-96.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) BMI Percentile Calculator for Child and Teen.

- L Aide aux Jeunes Diabétiques (2014) L’Association L’Aide aux jeunes diabétiques accompagne les familles.

- Mark A Sperling (2017) ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2014. International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes.

- Wang YC, Stewart S, Tuli E, White P (2008) Improved glycemic control in adolescents with type1 diabetes mellitus who attend diabetes camp. Pediatric Diabetes 9(1): 29-34.

- American Diabetes Association (2012) Diabetes Management at Camps for Children with Diabetes 35(Supplement 1): S72-S75.

- Gunasekera H, Ambler G (2006) Safety and efficacy of blood glucose management practices at a diabetes camp. J Paediatr Child Health 42(10): 643-648.

- Braatvedt GD, Mildenhall L, Patten C, Harris G (1997) Insulin requirements and metabolic control in children with diabetes mellitus attending a summer camp. Diabet Med 14(3): 258-261.

- Semiz S, Bilgin UO, Bundak R, Bircan I (2000) Summer camps for diabetic children: an experience in Antalya, Turkey. Acta Diabetol 37(4): 197-200.

- Hasan KS, Kabbanni M, Christensen R (2004) Mini-dose glucagons is effective at diabetes camp. J Pediatr 144(6): 834.

- Gandrud LM, Paguntalan HU, Van Wyhe MM, Kunselman BL, Leptien AD, et al. (2004) Use of the cygnus glucowatch biographer at a diabetes camp. Pediatrics 113 (1 Part 1): 108-111.

- Carlison KT, Carlson GW, Tolbert L, Demma LJ (2010) Blood glucose levels in children with Type1 diabetes attending A residential diabetes camp: A 2-year review. Diabet Med 30(3): 123-126.

- Soenggoro EP, Purbasari R, Pulungan AB, Tridjaja B (2011) Glycemic control in diabetic children and adolescents after attending diabetic camp. Paediatrica Indonesiana 51(5): 294-297.

- Leckie AM, Graham MK, Grant JB, Ritchie PJ, Frier BM (2005) Frequency, severity, and morbidity of hypoglycemia occurring in the workplace in people with insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetes Care 28(6): 1333-1338.

© 2018 Pravesh Kumar Guness. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)