- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

The Revitalisation of the Labour Movement in Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Algeria and Angola: The Use of ICT

Fransina Girley K1, Raqual Rego2 and Elsabé Keyser3*

1 Packaging Administrator, South Africa

2 University of Lisbon, Portugal

3 Industrial Psychology and Human Resource Management, North-West University, South Africa

*Corresponding author: Elsabé Keyser, Industrial Psychology and Human Resource Management, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences,North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Submission: June 13, 2017;Published: August 09, 2018

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume2 Issue4

Abstract

This study aims to conceptualise revitalisation of trade unions, trade union strategies, new information era and Internet use of trade unions internationally and in the five largest economies in Africa and present the use of the Internet as a strategy to prevent further challenges of trade union such as union membership decline and density. The research is based on the experience of a participant observer. The analysis based on historical development information, the related literature and documentation of the application of ICT. It has shown that there is slow progress of the ICTs by the unions of the top five economies in Africa due to the historical landscape they face. Trade unions are developing slowly and need to adapt to the use of the ICTs. The research focus was relatively narrow and focused on the ICT use and strategies of unions and more specifically unions in the five largest economies in Africa. This research is focusing on how unions are attempting to renew themselves through the use of Internet technology, networking and ICT. There were limitations in this research as there was a lack of availability of primary documentation and secondary analysis to evaluate and access the accuracy of observations and conclusions.This study will add value to trade unions particularly on the African continent to learn from and adapt to ICTs such as the website and Internet use.

Keywords: Trade unions; Cyber unions; Information communication technology; Strategies

Introduction

Globalisation and new technologies have significant impact on different organisations and trade unions are no exception. Trade unions in many countries are going through an institutional decline. This decline is due to the structural changes in labour force, economy and unemployment because of new technologies, labour market demographic changes and ageing population. Trade union reactions to the challenges of the existing situation are depicted through revitalisation [1]. Trade union strategies for renewal and revitalisation are a key issue [2-4].

Globally, this has led trade unions to develop new strategies to increase membership and resulted in the deployment of information and communication technologies (ICTs). ICT, such as the Internet used by trade unions, is one of its strategies to conduct more effective trade union functions to recruit members, campaigns, service provision, research, education and training [5-8].

Social media played an important role in Arab Spring countries, not only social media but also all digital technology such as Internet and mobile revolution. Furthermore, it plays a vital role in communication with people and it was almost impossible to communicate without the use of modern technology [9], but the question might arise whether African countries are using social media as well as the digital technology. The Internet used to gather information, social media to connect with people and global reporting such as news. Furthermore, ICT has played a significant role in Egypt and Tunisia but not a great role in Syria and Libya [9]. A discrepancy exists between researchers regarding strategy use of the Internet to prevent decline of membership. Lowery & Beadles [10] mention that trade unions have introduced the Internet as a means of strategy to avoid further challenges of trade union membership decline. Troy [11] argues that the use of the ICT will not improve trade unions and will surely not reverse the membership, density and influence trends.The use of ICT has problems and barriers for unions and their members as Lewis [12] mentions that “a lack of access to ICTs by both unions and their members is one of the key barriers inhibiting its widespread adoption and effective use, particularly in Africa”.

More recently, the researcher observed using social media has a robust potential for being a driving force for trade unions’ renewal, the use of ICT and the use of social media by trade unions is increasingly studied [13]. However, it is important to note that major differences exist in Internet use and accessibility among countries and regions. Within developing countries, there is a clear tendency towards increased concentration of information flows to urban and central areas, but there is limited research reported on the diffusion in areas of Asia and Africa [14].

Global trade unions started emerging with the use of the Internet since the beginning of the twenty-first century [15]. The global Internet origin was traced to the US-based ARPANET during the 1960s and Sub-Saharan Africa had the first network in 1988. Although mobile and Internet penetration remains comparatively low in Africa, pioneering countries were Tunisia and South Africa in 1991, Egypt in 1993 and Algeria and Zambia in 1994. By the end of 1997, 47 of the then 53 countries in Africa had some Internet access [16]. It has never happened in the history of the African continent that the population has been connected as it is today [17]. Nyirenda Jere & Biru [16] state that the Internet is showing growth on the African continent. The level of the internet penetration is above 20 percent and showing a growth. The mobile subscription is 70 percent and the internet subscription for mobile broadband access accounts is above 90 percent [16]. As emphasised by Rego et al. [18], ICTs are regarded as the most significant contribution for the revitalisation of trade unions. Moreover, ICTs are inexpensive, work quicker and are far-reaching compare to traditional communication; unions can overcome the problems of time, space and distance [19]. Furthermore, there is greater confidence among some trade unionists on the benefits of communicating online [20]. Previous research on revitalisation and the use of ICT mainly focuses on countries such as America, Europe, Portugal and the Anglo-Saxon countries.

The main objective of this article is to conceptualise how trade unions in the five largest economies in Africa are attempting to renew themselves by using Internet technology, networking and ICT. Furthermore, there are some advantages for conducting this research. First, it will help to fill in the gap concerning an investigation that is based on the Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Algeria and Angola context. These countries were chosen because they are the most economically active countries in Africa and the communities in these countries have ICT available such as Twitter, Facebook, Skype, Internet and mobile phones and ICTs to communicate with people [9]. Even if people in these countries have more access to ICT, there is still a lack of civic rights in these countries. It, therefore, is important to look at the labour relations systems and the decline of memberships in these countries.

Labour Relations Systems Decline of Trade Union Membership and Trade Unions in the Five Largest Economies in Africa

According to Burns [21], the decline in union membership started in 1945. Since the mid-1990s [22], there has been an ongoing discussion within trade movements on the appropriate strategies to reverse the decline of unions [23]. Wright [8] states that the analysis of trade union membership has continued to be regarded as an important topic, particularly in the field of labour relations and the economy of labour. In Anglo-Saxon countries, the loss of membership is a strong indicator of union decline [24]. Globally, trade union memberships are showing a massive decline and Africa is not an exception. Nigeria was under the countries dictatorship, but its level of union membership remained stable during 1980’s and 1990s [25].

The labour relations system of Nigeria

Nigeria is a country that has undergone political, social and economic fundamental changes. In 1960, Nigeria was in the process of a revolution after the departure of the British and it became an independent state [26]. The political and industrial relations structure that was left behind by the British and has changed dramatically within a period of six years. Moreover, the structure of trade unions remains unsatisfactory and most of them are ineffective [26,27]. The Nigerian industrial relations have failed due to governmental interference on policies and unpopular anti-labour law Genty et al. [28] state that the impact of globalisation, particularly the Internet, led to the decline in trade union membership density in Nigeria. The revitalisation strategies of the Nigerian trade unionare associated with the political parties. Nigerian trade unions have been working together with the political alliances to win the government power and labour legislation that favours them [28].

There are two trade union federations in Nigeria, namely Trade Union Congress (TUC) and Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC). The TUC has seven affiliate unions while NLC has 40 affiliate unions with about four million memberships [29]. In Nigeria, ICT is not used as part of trade union strategies due to the lack of the affiliate’s database. ICT plays a major role in different organisations to increase the productivity when employees are part of trade union membership. Therefore, trade unions should adapt to the use of ICT for the facilitation of effective and efficient administration.

The labour relations system of Egypt

In 1882, British occupied Egypt during the First World War. The national movement of Egypt rejected the British and attempted a revolution in 1919. Furthermore, Egypt gained its independence during 1992 [30]. Budhwar & Mellahi [31] that the high level of unemployment has a strong impact on the countries such as Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria and Morocco have said it. These countries are experiencing a strong union membership decline andthe legislation has limited their power. The reason that led to decline was the political background and the disappearance of the government in Algeria (the 1990s) and Egypt (1980s).

The Egyptian government has eliminated the trade union organisations and undermined the right of trade unions that are in the Constitution Article. The decision that was taken prohibited independent trade unions and considered them illegal organisations. However, many members said that they would fight the government’s decision, which will violate the country’s constitution [32]. This clearly shows that the trade unions, as well as the country, need ICT strategies to revitalise their organisations.

The labour relations system of South Africa

The South African industrial relations experienced major changes within a democratic period that were influenced by legislations. The post-apartheid government introduced the first act in order to address the workplace imbalances. Additionally, the following acts that was introduced are the Basic Condition of Employment Act of 1997, Skills Development Act of 1998 as well as the Employment Equity of Act of 1998.

Between the periods of 1980-2000, the registered trade union membership increased sharply from 782 000 in 1989 to three million in 2000, which was nearly 6 percent of the annual increase in South Africa [33]. Union membership increased after 1995 and it was much easier for the trade unions to register [33]. Barker [33] emphasises that union membership continued to grow up to 2002, but in that same year, there was a downward trend of union membership. Grobler et al. [34]; Barker [33] said that there is a decline of trade union membership. In 1999, the union membership was up to 55 percent (834,000 workers). However, it had increased to almost 70 percent (1.4 million workers) in 2014 [35].

South African trade unions and federations have gone through the strategic planning strategy regarding the trends of union membership years ago. Thus, some of the trade unions, as well as the federations, have failed to implement the new strategies to meet their challenges. This includes the NACTU affiliates who failed to maintain their bargaining council membership due to lack of representatives and being unable to implement decisions [36]. However, there are also affiliates in COSATU who failed to apply the decisions [37]. Other trade unions and federations have managed to develop the strategies of revitalisation of trade unions [38].

Union revitalisation has been a central focus for many organisations. Most research has concentrated on the new leadership and new strategic direction for unions [39]. Revitalisation strategies attempt to shift trade unions from the traditional movement unionism to social movement unionism [38]. The powerful social movement unionism took place in South Africa whereby trade unions were part of the coalition that defeated apartheid over the years [40]. In this sense, the coalition is a possible key for trade union revitalisation. Furthermore, South African trade unions have lost 17 000 members in a year [41]. Therefore, it is essential for trade unions in South Africa to revitalise their membership by using ICT, particularly the Internet.

South African trade unions used strategies of revitalisation suggested by Frege & Kelly [24], namely gaining union membership, restructuring of the organisation, employer’s partnership, political action, international associations and building a coalition. However, Dörre et al. [42] argue that organising unions should be considered from the power resource perspective to gain access to power resources. Pantland [43] states that South Africa is advanced with telecommunication infrastructure, which makes it possible for trade unions to use ICT. However, the penetration of the Internet is too low, especially when trade unions are not making full use of the Internet possibilities. Furthermore, Pantland [43] believes that there is a significant ICT potential to facilitate the union revitalisation. Thus far, trade unions have failed to make use of and keep up with the technological advances.

The labour relations system of Algeria

The establishment of independent unions was introduced by the Algerian Industrial Relations Law (90-14) of 1990, which requires trade unions to use the authority of declarations. The governor or the labour minister will issue the receipt or letter of acknowledgement to the trade union within 30 days. Therefore, if trade unions do not have the receipt, they cannot operate legally [44]. Horwitz & Budhwar [45] argue that the Algerian trade union had a strong union membership, but the legislations, as well as the market dynamics, have been severely reducing their power and political influence.

The labour relations system of Angola

The General Labour Act 2/2000 of February 11 governs the Angolan labour relations. The Act separates the legislations that deal with the aspects of labour relations. There are mechanisms that limit the authority of parties to employment relationship. However, the Angolan labour legislation includes aspects such as the working hours, type of contract, flexibility and so forth [46]. Angola has improved dramatically with the use of ICTs. Despite the improvement, the political rights, as well as the liberties, are still controlled by the Movement for the Liberation of Angola-Labour Party (MPLA) [47].

According to Wilson [48], trade union membership in Angola is unknown. Angolan trade union membership is limited because when National Union of Angolan Workers (UNTA) and General Centre of Independent and Free Unions of Angola (CGSILA) are combined, they have less than one million members.Trade unions and collective bargaining in countries like Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt and Morocco have become undesirable [45]. Algeria has to build the democracy on respect for their individual and collective rights, particularly on the rights of its workers and unions. Algerian unions that are not ruled by the government are faced with unfair dismissals, intimidation and even imprisonment [49].

ICT and Revitalisation: Old and New Methods

The ICTs are a significant contribution of union revitalisation especially in the Anglo-Saxon countries because it has an impact on both internal and external communication [50]. According to Fiorito et al. [51]; Kombol [52], the use of online communication has been observed among the trade unions. For instance, Diamond & Freeman [53] mention attraction of new members and improvement of services.Frege & Kelly [24] state that for the renewal and revitalisation of the labour movement, trade unions needs to improve their recruitment structure to attract new employees. Lowery et al. [54] point out that for trade unions to attract new members as well as reversing the union membership decline; they must change their old methods and be willing to try new methods. Table 1 shows the methods that were used in the past and the current methods, which was introduced by the use of ICT.

Table 1:ICT old and new methods used by trade unions.

Fuchs [55] states that the implementations of the new ICTs are associated with risks, such as employer counter-mobilisation [56]. However, Greene et al. [57] emphasise that the Internethas an impact on the internal and external communication of the trade unions. The internal communications are e-learning, providing services to members, promoting access to more information, while the external communication is to foster national as well as international solidarity and ensure that they can contact mass media [57]. According to Fioritor et al. [21], trade union organisations feel that the introduction and implementation of ICT is critical for the success of their organisation and that the use of the website as well as an email will provide trade union members and the public a platform to raise their voices [20]. However, Pinnock [58] emphasises that the use of the ICT be considered as being too slow and uneven. The potential of ICTs used as internal communication to trade unions in empowering their structure [53]. Martinez Lucio [59] argues that the users’ profile may be ineffective because they are computer illiterate and are resistant to adapt to the new forms of communication.Research indicates that there has been a growth in the use of new ICTs within trade unions in unions’ action such as campaigns, bargaining, announcements based on training, collective agreements, developments, strikes and shop stewards [50,53].

Diamond & Freeman [53] argue that the ICTs offer new ways for trade unions to strengthen their union movement and engage with members. The question might arise on how ICT will help trade unions to reverse the decline of union membership. Furthermore, Freeman [60] points out that ICT such as the use of the Internet and website can help trade unions to revitalise union membership and union influence as it is cheaper.Some researchers argue that the use of new online technology can be an important tool for unions [61] and are confident with communication online benefits [20], while some have regarded the possibilities of digital media as a weapon that changes the conditions of the trade unions; for example, information on the Internet and social media is limited [5]. Masters [61] states that there had been a disagreement between the researchers and observers on the benefits of ITC to organise unions.

Fiorito & Gallagher [62] state that some researchers failed to use the potential of the Internet tool for organising unions. It has been shown that the development of information technology among unions is very slow and their interest in membership is limited [63,64]. The internal communications (email, intranet) and external communication (websites and emails) allow unions to exchange information easily and timorously, unlike the traditional way of communication that focuses more on the chat rooms and discussion boards [50]. Trade unions in United States of America and the United Kingdomstarted to use the Internet for union activities [60]. The number of union websites in Europe includes the United Kingdom with 373, France with 181 and Germany with 59.

The use of union website has risen rapidly, particularly in developing countries as unions have gone online. Global Union Federations, as well as the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, consider the Internet an important weapon for their union activities [60]. Previous studies have examined the impact of ICT on trade union communication, more especially on the websites and emails and evaluated the extent to which the transformation of unions has been taking place. Fiorito [65] have explored the performance outcome of a trade union by using of ICT as the tool. Their findings were found positive for union organising measures (change in trade union membership), while the characteristics of trade union and environmental variables were considered strongly related to the use of ICT. In the study of Greer [66] on the analysis of union websites in the United States, the focuses on the information provision rather than opportunities for engagement. The increase of leadership, the use of ICT and the improvement of communication are regarded as important trends for the trade unions.

According to Bryson et al. [67], the online networks such as Facebook managed to attract more members in a short period. Many employees often use social media and their networking features for the purpose of voicing concerns about work-related issues and connecting with their colleagues. In fact, Masters et al. [68] found that United States union members are strong users of ICT.

White [69,70] states that union campaigns as well as social engagement serve as guidelines that highlight the importance of union awareness, informed channel selection, consistency and monitoring. However, it is not yet known which of the trade unions are more likely to prioritise social media [71]. The question can arise, will unions move towards professional networks such as LinkedIn and Twitter, upload photo and video sites to retain communication among them?The potential of ICT to improve trade union communications has been of global interest for the past years. Lee [5] states that the development of the Internet highlights positive views on how online communications can become a force of change for trade unions; however, Chaison [72] has criticised the use of the Internet as not beneficial and it might become destruction to some of the members. ICT has opened new opportunities for trade unions, but on the other hand, it is seen as threats to its members [71].

Trade union membership ascended in the 1940s and 1950s and benefited from having contemporaneous forms of common experience [67]. Gerbaudo [73] said that some tools are associated with the protest action in Egyptian revolution of 2011 such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Thus, what is preventing modern trade unions from attracting millions of members with Facebook? Oruh [74] suggests that the use of social media such as Twitter, Facebook and Blogs by Nigerian trade unions could be effective in increasing the employees’ voice. The findings have shown that Nigerian trade unions prefer the Short Message System (SMS). The usage of mobile phones in Nigerian trade unions has shown growth. The use of mobile phone increases the ability for an adult to send and receive text messages for participation in union activities. Additionally, the trade union leaders and members believe that the SMS usage is effective and empowering [75]. Nwagbara et al. [76] state that Nigerian trade unions are shaped by the use of social media.

Egyptian trade unions gain information, updates on the latest news and interact with others by using Facebook and Twitter [77]. Baglione [35] said that Egypt played a significant role in influencing Algerian unions to use Facebook, but many unions did not use it. The International Telecommunications Union state that the Algerians had Internet access of 12.5 percent in 2010.People in Angola can access Facebook, YouTube, Blogs and Twitter freely. The Internet penetration of Angola in 2014 was 21 percent. The access to amobile phone in Angola has increased from 62 percent in 2013 to 63 percent in 2014 [78]. African News Agency [79] states that Cosatu, the South African trade union federation, had shown an interest in Twitter and Facebook. However, some of its trade unions still lag behind and do not use Twitter and Facebook effectively.The new ICT became an important source for communication that can transfer information (email and website) and allow the users to interact using Web 2.0 (social media, forums and interactive sites). Web 2.0 can be defined as a stage whereby the user can interact using social media, interactive website and teleconferencing [13].

Vielhaber & Waltman [80] state that even though many trade unions worldwide have adopted the new ICT, there is still a need for personal face-to-face communication that builds a strong relationship between the unions and motivates people to use emails and update their websites. According to [13], there are limited studies based on the potential of new ICT and Web 2.0. However, almost all unions have a website and only few trade unions allow the two-way communication opportunity such as online interaction [19]. Masters et al. [68] emphasise that trade unions should strategically invest in education and train members to benefit in IT. Secondly, unions should be able to identify their members who are high-intensity users of IT. Thirdly, unions must be aware that their membership falls into two broad categories: networked and nonnetworked. Lastly, union members must ensure that there is strong communication among them.

Therefore, the ICTs are a significant contribution of union revitalisation especially in the Anglo-Saxon countries because it has an impact on both internal and external communication [50]. Trade unions see the use of the IT as one of their strategies [81] and it provides information via emails and websites for its members and the public [20]. Trade union revitalisation is very difficult,it is a slow process for the union and it involves internal change [58]. The roles of unions should be re-negotiated. Cockfield [81] points out that the potential use of ICTs are shaped by how unions deal with the internal political processes; however, it does not mean ICTs will not have a positive impact on union revitalisation. The ICTs contribution to trade union revitalisation should not be dismissed. Hogan & Greene [82] and Diamond & Freeman [53] explain that ICTs should be part of union renewal strategies.

Strategies for Revitalisation

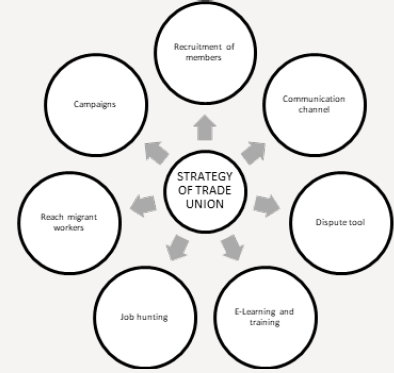

Based on the strategic choice perspective [83], trade unions need to implement a particular strategy for the purpose of its revitalisation [24]. Concerning the challenges that trade unions are facing, they may adopt some combination of strategies. Frege & Kelly [24] describe the six broad strategies used by trade unions to revitalise themselves, namely organising, labour-management partnership, political action, restructuring, social movement unionism and international unionism [24]. When implementing these strategies, trade unions are trying to shift their focus from the traditional way to the new way of using IT [84-87]. The following strategies for the use of websites by unions are identified in the work of Bibby [84] in Figure 1.

Figure 1:Strategies used by trade unions (Compiled by researcher).

Website to recruit new members

Bibby [84] explains that potential members can be reached through trade union websites. On the website are forms the members can complete and are able to pay their first membership subscription via the mechanism of the website [84]. As White [88] states, union membership among young people is low and young individuals use media through multiple channels. He further mentions that unions that want to recruit young people to the unions need to invest in relevant and modern creative graphic design and adapt to it [88].

Website as a communication channel

Communication is one of the main roles for trade union websites to communicate with their union members. Lawrence [89] emphasise that the interaction of trade union members either on websites or between themselves is essential for the union website. The more trade unions members interact with each other, the better the sense of togetherness. Moreover, for the trade unions to loginto the website, their name and password registration will be required to enter and enjoy the services offered such as online training, discussion forums, internal union information and so forth [89].

Website as an industrial dispute tool

The potential of electronic communications is an important tool during the industrial disputes and it was highlighted at an early stage of the development of the Internet [84]. Diamond & Freeman [53] stated that the Internet had been used by unions to conduct their labour dispute. This is done by emailing their members or presenting the union case on the public over the Internet. The website allows unions to access it at low cost as well as informing members or public about the bargaining issues [53].

Website as part of e-learning

According to Bibby [84], trade unions were offering traditional training as well as learning opportunities to their members. However, trade unions are exploring the potential of using the website content for online learning that includes the training material found over the Internet.

Website to assist members to find work

In the past, many trade unions played an important role to ensure that their union members found work. The craft-based union used the traditional method and discovered the potential of the Internet use. Vacancies are advertisedonline and members have to complete the registration form and upload their CV online. It is encouraged that union members who are leaving their employment should maintain loyalty to their unions [84]. International unionism and liberalisation have led to the increased mobility of capital. The introduction of IT and knowledge process outsourcing (KPO) has resulted in leveraging low cost of labour particularly on emerging economies and developing countries [90]. Watermen link the new labour internationalism to ICT and he asks the question if the labour communication using computer will bring on a fifth international. Leischa [91] mentions cyber union website as the potential of the ICTs to revitalise trade unions and to allow unions to communicate with each other directly.The ICTs or cyber unions are seen as the use of new spaces rather been seen as putting it in space as a tool for revitalisation. Pantland [43]; Leischa [91] identify two strategies for union revitalisation using ICT, namely top-down strategies and bottom-up strategies.

Top-down strategies

Trade unions have a history towards technological change as change damaging them. Technology played a major role in causing trade union crisis and complicated the attitude of unions in using technologies as part of organising. Lommerud & Straume [92] said that they do not blame trade unions and they are correct by concluding that the technological changes have an impact on them. Trade unions have a historyof technological development [93], with regard to the need to improve productivity, cutting costs and increasing profits; however, unions have long recognised the potential of offering work to its members [94]. Since industrial revolution began, people have lost their jobs; deskilling and flexibility increased due to new technology. Pantland [43] emphasises that the most common response of trade unions to the use of ICT is the Web 2.0 e.g. interactive such as social networks, during the first stage of the development. Furthermore, trade unions who embraced these technologies appeared to use them without any clear understanding or strategy. Bélanger [95] used ICT to educate unions in developing countries.

Darlington [96] said that trade unions have to adapt to the new technology for their survival and ignoring the potential of ICT is not an option. Union leaders are aware that the potential of ICT will provide the renewal with the movement and attract new members; however, they are worried that this new technology will undermine their powers [57]. According to Pantland [43], the top-down strategies have created the online joining facilities that will allow people to join online rather than downloading the forms.

These facilities will advertise online, post news online and search engines will be available to type the keyword of what they would like to see on the website. However, these strategies bring problems, for instance, isolation of members and lack of representative structure in the workplace. Hogan & Greene [82] feel that the use of ICTs is educational and becoming easier to master, particularly the Web 2.0 and Web 3.0. Many trade unions are using the lifelong strategies that provide free courses in ICTs to trade unions and are delivered by the union tutor in the working environment [91]. Thus, these learning programmes tend to increase the union membership and branches grow in confidence.

Bottom-up strategies

The potential democratising activity of ICT is important. As mentioned by Schradie [97], the bottom-up strategy is a participatory democratic approach where members participate on issues. Hogan & Greene [82] mention that bottom-up strategy views are because individual members’ abilities are enhanced when websites are established by trade unions. Members can then have more frequent and direct access to union elites. Members can communicate their opinions on organisational structures and policy matters. Members can also have input into electronic meetings and virtual discussions [63]. The problems experienced with bottomup strategies are that members can publish their opinions and their views and opinions might differ from the official union line.

ICTs are a solution to solve union’s problems such as union membership [10]. Diamond &Freeman [53] state that it hadbeen argued that ICTs offer trade unions a new way to communicate with members and strengthen the union movement on both a national and international scale. The e-unions and cyber unions are the terms that describe the new form of trade unions that arose because of this technological revolution [6,96]. Greene et al. [57] state that the new technologies are educational, provide skills and are easier to use. Barbrook’s [98] finding shows that people use the potential of ICTs to communicate in different projects of unions and communities. ICTs facilitate decentralised networks and trade unions need to adapt to the use of these to survive [95].

The use of ICTs offers many opportunities to trade unions. Unfortunately, two-way interactivities such as Twitter are used to publish press releases and not to communicate with their members and non-members. Therefore, they are missing the fact that the purpose of using Twitter was to revitalise unions by sending union messages to activists [91]. In order to face this crisis, trade unions must begin to develop a strategy for reversing the decline in union membership and density. The implementation of new agendas, the revitalisation of the leaders and the use of the ICTs are considered as other strategies for trade unions [99]. The trade unions have to revitalise strategies to reverse the decline of membership.

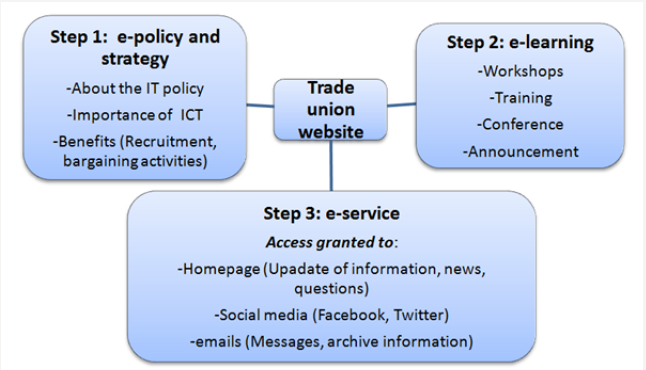

Union strategic model

The researcher of this study has developed the model based on the strategies of the trade union to renew and revitalise their organisation with the potential of ICTs, particularly on the website of the trade unions. This model consists of three steps, namely e-policy and strategies, e-learning and e-service. These steps will assist trade unions to use websites and adapt to the potential of ICTs.

E-policy and strategy: In this step, e-policies must be developed in a strategic way and must be clear and understandable by the trade unions. An e-policy must have information that will give a brief about the ICTs, the importance of ICTs as well as the benefits of ICTs. Unions should know what is expected from them when they read the policy. This step will limit union leaders from using money to print policies, thus their members could view policies online.

E-learning: E-learning is one of the important steps to take into consideration and plays a huge part in our daily lives. This will be a platform for trade unions to learn for themselves and learn from others. For the trade unions to learn their union website, they should attend workshops, trainings, conferences and meetings online by logging in with their registered details; this will save time looking for a venue or travelling far to a meeting.

E-service: The service of the members is to provide online such as updating personal information, asking questions and providing suggestions. Furthermore, trade union members will have access to the union websites, emails and using communication networks such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Skype. The use of the Internet is faster and cheaper, therefore, e-service will meet the union’s demands (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Union strategic model (Adapted by the researcher).

Research Methodology

The literature review was conducted based on a systematic search process by using the national and international sources, namely journals, textbooks, newspaper reports, Internet-based search engines (Google Scholar, Google), as well as the relevant dissertations.

Research participants

The sample consists of trade unions from the top five economies in Africa. The trade unions used for this study were selected from Google search engine and the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) list.Numerous Internet searches were performed using Google to search for trade unions within the five largest economies in Africa by analysing the website, the front page or the home page of the trade union. Keywords such as name of each country and unions or federations were used. The researcher identified 90 trade unions for the five largest economies in Africa with their own websites; thus, there are 308 trade unions that do not have websites; the total number of trade unions in Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Algeria and Angola is 398.

Findings

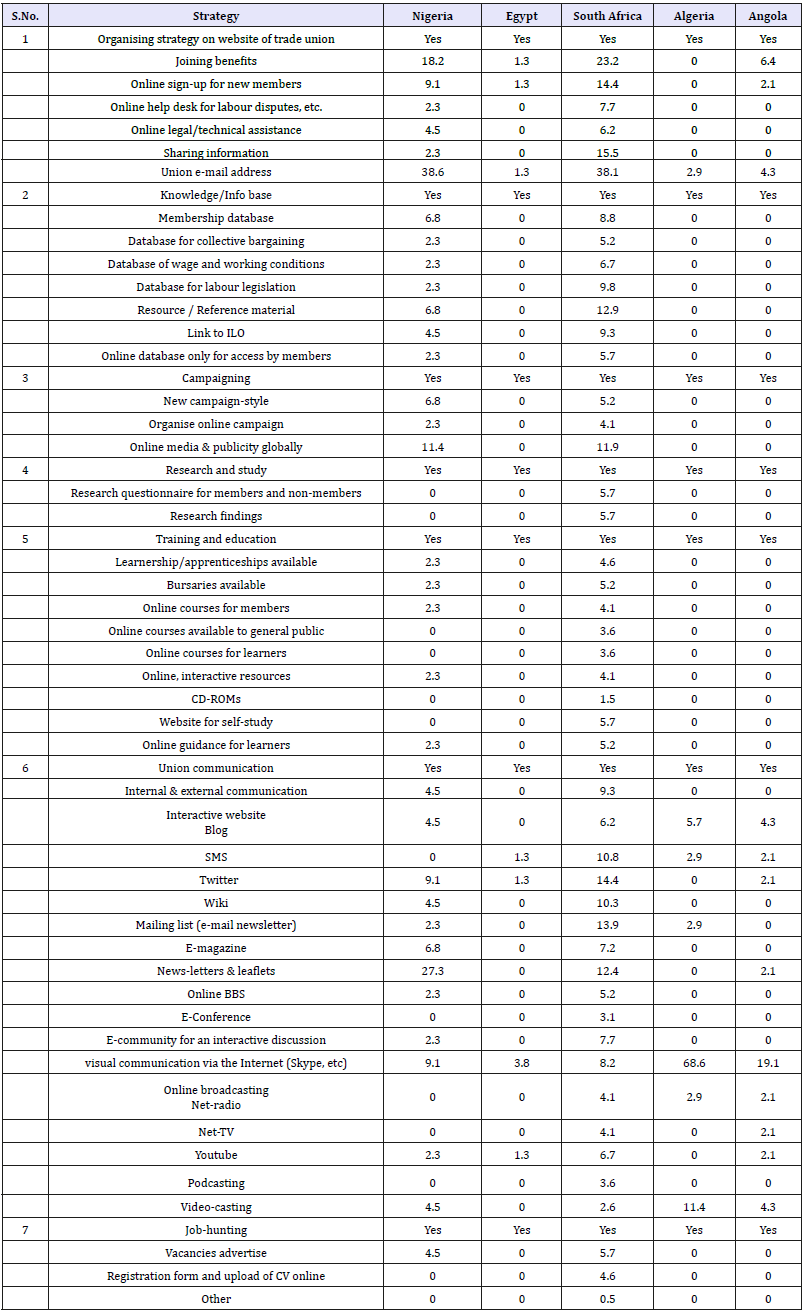

Only certain trade unions have dedicated websites within these five countries. These selected countries have different languages used in their websites, but the Google translator was used as a tool to overcome the language barrier. It is important to use the selected countries, as they are the top five economies in Africa. The aim is to explore if those countries are advanced in economic status only or also in the use of ICT. The typology of Rego et al. [19] was used to monitor the relationship between trade unions and the Internet. Furthermore, the typology of Schradie [97] explained the top-down strategies and bottom-up strategies. Top-down strategies emphasise unions had much more of an active Internet presence but technology played a vital role in complicating unions organising. Furthermore, bottom-up strategies had low levels of digital engagement. The unions see the Internet as one of many tools that organise the powerless rather than a way of reaching the powerful.The numbers in the Table 2 represent the percentage of trade unions that use the stated strategies. The number of trade unions per country that were found is as follows: Nigeria (43), South Africa (194), Egypt (79), Algeria (35) and Angola (47). The below Table 2 shows a comparison of different strategies based on the use of ICT per country.

Table 2:Strategy on website of trade unions.

It is clear that a gap exists between the websites and the manner in which trade unions connect with their members and non-members. Nigerian and South African trade unions make more use of those ICTs strategies, while Egypt, Algeria and Angola still use traditional methods.In organising strategy, trade unions in Nigeria (38.6%), South Africa (38.1%) and Algeria seem to be using union email addresses and Angolan trade unions include the benefits of joining (6.4%) on their website for members and non-members. Egyptian trade unions are using the union email address (1.3%), online sign-up for new members (1.3%) and include the benefits of joining online (1.3%). This indicates that majority of trade unions still prefer to use the email addresses.

The trade unions in Nigeria and South Africa use the knowledge or information base strategies. Nigeria uses membership base (6.8%) and resource or reference material (6.8%), whereas the South African trade unions use resource or reference material (12.9%). Most of the trade unions do not include their membership database on their website.Trade unions use online media and publicity globally, such as Nigeria (11.4%) and South Africa (11.9%). Campaigns are very important in attracting new members to unions in Nigeria (2.3%) as well as in South Africa (4.1%). Online campaigns are the least they can use; however, Egypt, Algeria and Angola trade unions do not consider using the campaign strategy. The research findings of South African unions shows that there is (5.7%) for research study and (5.7%) research questionnaires, but the unions in Nigeria, Egypt, Algeria and Angola does not show any interest in the research and study strategy.

Nigerian trade unions seem to be using most of the training and education strategies. The website content of Nigerian trade unions is 2.3% of the learner ship or apprenticeships available, bursaries available, online courses for members, online interactive resources and online guidance for learners. Trade unions in South Africa have used the self-study (5.2%). Furthermore, Egypt, Algeria and Angola did not invest in the training and education strategies. Communication is one of the important union strategies. Nigeria trade unions use newsletters and leaflets (27.3%) as part of their communication. Egyptian (3.8%) and South African (14.4%) trade unions have used twitter, while trade unions in Algeria (68.6) and Angola (19.1%) are using visual communication via the Internet such as Skype, Facebook, and LinkedIn. South African (5.7%) and Nigerian (4.5%) unions to advertise vacancies on their websitefor the benefits of its members and non-member have used job-hunting strategy.

The web presence of trade unions varies according to the countries. It seem that in all five countries, the minority of trade unions have the website but do not use it for union activities such as communicating, campaigns, general union movements and so forth. The findings indicate that the trade unions of five largest economical African countries still lack communication strategies because unions do not have the skills to use the ICT and Internet in order to deal with the new and old challenges [100]. It has been shown that the strategies of organising, knowledge/info base, campaigning, research and study, training and education, union communication and job-hunting have not been used by many trade unions; the statistics show that few Nigerian and South African unions are using those strategies; however, most unions in Egypt, Angola and Algeria consider others as their strategies.The way trade unions have used the Internet, particularly the website content does not contribute to the revitalisation of trade unions. It can be said that trade unions in Egypt, Algeria and Angola benefit less than trade unions in Nigeria and South Africa from the potential offered by ICTs, due to web presence.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study outlines the historical and the current landscape of the trade unions particularly on the potential of the ICTs. According to Nepgen [101], it is important for the trade unions to restructure the way they view their union members, officials’ roles and organisational functions. Trade unions must observe how other organisations are using the ICTs and how they are applying ICT techniques as part of their benefits. It is clear from the above, that trade union organisations are faced with a dramatic decline in union membership and trade unions need to find a solution to reverse this decline; however, trade unions argued to organise their unions by using the potential of the ICTs [102].

The Nigerian and South African unions take more advantage of the Internet than unions in Egypt, Algeria and Angola. Nigerian and South African trade unions are using website as a union life and social network.

The primary findings indicate that Nigeria is on 38.6 percent organising strategy by creating a union e-mail address. South Africa has 12.9 percent of knowledge information based on resource or reference materials and leads with 12.9 percent campaigning online media and publicity. South Africa is on 5.7 percent for the research questionnaire, job hunting as well as training and education. The union communication in Nigeria is 27.3 percent based on the newsletter and leaflets.

Nigeria has been working with the political alliance to get favourable legislations and government power, which led trade unions not to use ICT strategies due to the lack of affiliation databases [28]. South Africa had strategic plans to combat the decline of union membership, but their strategies have failed [38].

In Egypt, the right of the trade union in the constitution has been undermined and the government has eliminated the trade unions [31]. On the other hand, trade unions in Algeria are faced with the political government and the disappearance of the government during 1990s led unions to experience a decline in membership [32].

Furthermore, the Liberation of Angola Labour Party (MPLA) controls the political rights and the liberties of the unions. However, Angola has improved on the potential of ICTs (Freedom on the net, 2013).The use of the ICTs has the potential to transform the trade unions and contribute to union revitalisation. Trade unions have not met the potential of ICTs to facilitate renewal and revitalisationwithin their organisations because some unions are ruled by the government.

References

- Krašenkienė A, Kazokienė L, Susnienė D (2014) Relationships of the trade unions with the media: The lithuanian case. Administrative Sciences 4: 1-14.

- Behrens M, Hamann, K, Hurd R (2004) Conceptualizing labour union revitalization. In: Frege C, Kelly J (Eds), Varieties of Unionism, Strategies for Union Revitalizations in a Globalizing Economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 11-29.

- Frege CM, Kelly JE (2004) Varieties of unionism: Struggles for union revitalization in a globalizing economy. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Hyman R (2013) European trade unions and the long march through the institutions. In: Fair brother P, Lévesque C, Hennebert MA (Eds.), Transnational trade unionism: building union power. Routledge, London, England, pp. 161-179.

- Lee E (1997) The labour movement and the internet - The new internationalism. Pluto Press, London, England.

- Shostak AB (1999) Cyber union: Empowering labour through computer technology. ME Sharpe, Armonk, New York, USA.

- Wellman B (2001) Physical place and cyber-place: The rise of personalised networking. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 25(2): 227-252.

- Wright CF (2011) The role trade unions in future workplace relations. Acas Publication, University of Cambridge, UK.

- Eriksson M, Franke U, Granåsen M, Lindahl D (2013) Social media and ICT during the Arab Spring.

- Lowery CM, Beadles NA (2006) Evaluating the usability of union web sites in the United States: A case study. Communications of the IIMA 6(2): 99-106.

- Troy L (2003) Is the future of unionism in cyberspace? Journal of Labour Research 24(2): 251-210.

- Lewis C (2005) Unions and cyber-activism in South Africa. Critical perspectives on international business 1(2-3): 194-208.

- Rego R, Sprenger W, Kirov V, Thomson G, Di Nunzio D (2016) The use of ICTs in trade union protests-five European cases.

- Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 22(3): 315-329.

- Furuholt B, Kristiansen S (2007) Internet Cafés in Asia and Africa- Venues for education and learning.

- Lee E (2003) How the Internet is changing unions. Labour Start, USA.

- Nyirenda Jere T, Biru T (2015) Internet development and Internet governance in Africa. Internet society, USA.

- Yonazi E, Kelly T, Halewood N, Blackman C (2012) The transformational use of ICTs in Africa. eTransform Africa, USA, pp. 1-28.

- Rego R, Alves PM, Naumann R (2010) Different information and communication strategies and the revitalization of trade unions: The case of the Portuguese public administration sector.

- Rego R, Alves PM, Naumann R, Silva J (2014) A typology of trade union websites with evidence from Portugal and Britain. European Journal of Industrial Relations 20(2): 185-195.

- Stevens CD, Greer CR (2005) E‐Voice, the Internet, and life within unions: Riding the learning curve. Working USA 8(4): 439-455.

- Burns J (2010) Strike: Why mothballing labour’s key weapon is wrong. New Labour Forum 19(2): 59-65.

- Roberto P (2010) Trade union strategies to recruit new groups of workers. Eurofound, Ireland, pp. 1-51.

- Lynch S, Pyman A, Bailey J, Price RA (2009) Union strategies in representing ‘new’ workers: the comparative case of UK and Australian retail unions. In 15th world congress of the International Industrial Relations Association (IIRA): The new world of work, Organisations and Employment, Sydney Convention and Exhibition Centre, Sydney, Australia.

- Frege CM, Kelly J (2003) Union revitalisation strategies in comparative perspective. European Journal of Industrial Relations 9(1): 7-24.

- Tokunboh M (1985) Labour movement in Nigeria, past and present. Lutterand Publications, Ikeja, Nigeria.

- Adeniji MA (2015) An analysis of industrial relations practice in Nigeria and Ghana (similarities and differences in their systems). Global Journal of Researches in Engineering: Industrial Engineering 15(1): 43-44.

- Adebisi MA (2013) History and development of industrial relations. Hybridity of Western Models Versus Military Interventionism Culture, Nigeria 4(14): 687-692.

- Genty KI, Adekalu SO, Ajede SA, Oludeyi OS (2013) Globalisation and trade unions challenges: Nigerian manufacturing sector experience. European Journal of Business and Management 5(17): 20-29.

- Kalusopa T, Otoo KN, Shindondola-Mote H (2012) Trade union services and benefits in Africa.

- Al Kassab KIM (1977) A comparative study of industrial relations in Iraq, Egypt and Syria. Edinburgh Research Archive, UK.

- Budhwar P, Mellahi K (2006) Introduction: HRM in the Middle East Context. In: Budhwarand P, Mellahi K (Eds.), Managing Human Resources in the Middle East, Routledge, London, pp. 1-19.

- Hassan K (2016) Egyptian State takes on independent Trade Unions.

- Barker F (2007) The South African labour market: Theory and practice (5th edn), Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Grobler P, Wärnich S, Carrell MR, Elbert NF, Hatfield RD (2006) Human resource management in South Africa. Thomson, London, England.

- Baglione LA (2016) Writing a research paper in political science: A practical guide to inquiry, structure, and methods: SAGE Publications, UK.

- NACTU (2001) Report on Activities, 6th National Congress

- COSATU (2003) Organisational review COSATU, Braamfontein, Johannesburg. Consolidating Working Class Power for Quality Jobs: Towards 2015. Discussion document for the COSATU 8th National Congress.

- Webster E, Buhlungu S (2004) Between marginalisation and revitalisation? The state of trade unions in South Africa.

- Turner L, Katz H, Hurd R (2001) Rekindling the movement: Labour’s Quest for 21st Century Relevance. ILR Press/Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

- Phelan C (2011) Trade unions, democratic waves, and structural adjustment: the case of Francophone West Africa. Labour History 52(4): 461-481.

- Rand Daily Mail (2015) Unions lose 17‚000 members in one year: Stats. Times LIVE, South Africa.

- Dörre K, Holst H, Nachtwey O (2009) Organizing-A strategic option for trade union renewal. International Journal of Action Research 5(1): 33- 67.

- Pantland W (2010) Cyberunions: New technologies, distributed discourse and union renewal.

- Chelghoum A, Takeda S, Wilczek B, Homberg F (2016) The challenges and future of trade unionism in Algeria: A lost cause?

- Horwitz FM, Budhwar P (2015) Human resource management in emerging markets: an introduction. In: Horwitz FM, Budhwar P (Eds.), Handbook of human resource management in emerging markets. Cheltenham UK & Northampton MA. Edward Elgar Publishing, Chap, USA, pp. 1: 1-10.

- Cuatrecasas GP (2013) Angola investment guide: Legal and tax aspects. Cuatrecasas Goncalves Pereira, Luanda, Angola.

- Freedom on the Net (2013) Angola.

- Wilson Z (2006) The United Nations and democracy in Africa: labyrinths of legitimacy. Taylor and Francis Group, New York.

- Equal Times (2016) Algeria: human and trade union rights activists under pressure. Equal Times, Belgium.

- Greene AM, Kirton G (2003) Possibilities for remote participation in trade unions: Mobilising women activists. Industrial Relations Journal 34(4): 319-333.

- Fiorito J, Jarley P, Delaney JT, Kolodinsky RW (2000) Unions and information technology: From luddites to cyber unions? Labor Studies Journal 24(4): 3-34.

- Kombol MAV (2014) Uses of Social Media among Selected Labour Unions in Abuja during Nigeria’s (January 2012) Oil Subsidy Removal Protests. Studies in Media and Communication 2(1): 102-114.

- Diamond WJ, Freeman RB (2002) Will unionism prosper in cyberspace? The promise of the internet for employee organization. British Journal of Industrial Relations 40(3): 569-596.

- Lowery CM, Beadles NA, Faulk LH (2008) Assessing the usability of union website. Communication of IIMA 8(3): 49-56.

- Fuchs C (2014) Digital Labour and Karl Marx. Routledge, New York, USA

- Upchurch M, Grassman F (2015) Striking with social media: The contested (online) terrain of workplace conflict. Organisation 23(5): 639-656.

- Greene AM, Hogan J, Grieco M (2003) E-Collectivism and Distributed Discourse: New Opportunities for Trade Union Democracy. Industrial Relations Journal 34(4): 282-289.

- Pinnock SR (2005) Organizing virtual environments: National union deployment of the blog and new cyberstratejpes. Working USA 8(4): 457-468.

- Martinez Lucio M (2003) New communication systems and trade union politics: a case study of Spanish trade unions and the role of the Internet. Industrial Relations Journal 34(4): 334-347.

- Freeman RB (2005) From the webbs to the web: the contribution of the internet to reviving Union Fortunes. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, England.

- Masters MF (2013) Guest editorial preface: Special section on Unions, information technology and knowledge workers. International Journal of E-Politics 4(4): 4-6.

- Fiorito J, Gallagher DG (2013) Distrust of Employers, Collectivism, and Union Efficacy. Journal International, Journal of E-Politics 4(4): 13-26.

- Ward S, Lusoli W (2002) Dinosaurs in cyberspace? British trade unions and the Internet. European Journal of Communication 18(2): 147-179.

- Gibney R, Zagenczyk T, Masters MF (2013) The Face (book) of Unionism. International Journal of E-Politics (IJEP) 4(4): 1-12.

- Fiorito J, Jarley P, Delaney JT (2002) Information technology, US union organizing and union effectiveness. British Journal of Industrial Relations 40(4): 627-658.

- Greer CR (2002) E-voice: how information technology is shaping life within unions. Journal of Labour Research 23(2): 215-235.

- Bryson A, Gomez R, Willman P (2010) Online social networking and trade union membership: What the face book phenomenon truly means for labour organizers. Labour History 51(1): 41-53.

- Masters MF, Gibney R, Zagencyk TJ, Shevchuk I (2010) Union members’ usage of IT. Industrial Relations 49(1): 83-90.

- White A (2010) Social media for unions. Aleithia Media and Communications. Online report.

- White A (2012) Guide to online campaigning for unions: everything a non-expert need to take an online union campaign from start to finish. Online report.

- Panagiotopoulos P, Barnett J (2015) Social media in union communications: An international study with UNI global union affiliates. British Journal of Industrial Relations 53(3): 508-532.

- Chaison G (2005) The dark side of information technology for unions. Working USA 8(4): 395-402.

- Gerbaudo P (2012) Tweets and the Streets: Social media and contemporary activism. Pluto Books, London.

- Oruh ES (2014) Giving voice to the people: Exploring the effects of new media on Stakeholder Engagement in the Nigerian trade union movement. Management Research and Practice 6(3): 41-52.

- Christian O (2015) The impact of social media on political influence and policy outcomes: The Nigerian experience, Michigan, USA.

- Nwagbara U, Pidomson G, Nwagbara U (2013) Trade unions and leadership in Nigeria’s new democracy: Issues and Prospects. Economic Insights-Trends and Challenges, pp. 33-40.

- Abdulla R (2014) Egypt’s media in the midst of revolution. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, USA.

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU) (2000-2014) Mobilecellular telephone subscriptions.

- African News Agency (2015) Cosatu leadership to get social media accounts.

- Vielhaber ME, Waltman JL (2008) Changing uses of technology: Crisis communication responses in a faculty strike. The Journal of Business Communication 45(3): 308-330.

- Cockfield S (2005) Union renewal, union strategy and technology. Critical perspectives on international business 1(2-3): 93-108.

- Hogan J, Greene AM (2002) E-collectivism: Online action and online mobilization. In: Holmes L, Hosking DM, Grieco M (Eds.), Organising in the Information Age. Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot, England.

- Kochan T A, Katz HC, Mc Kersie (1986) Transformation of American Industrial Relations. Basic Books, New York, USA.

- Bibby A (2004) International trade union activity and work of works councils of the internet. A report for int unity.

- Heery E, Adler L (2004) Organizing the unorganized. In: Freje C, Kelly J (Eds.), Varieties of unionism: Strategies for union revitalization in a globalizing economy. Oxford University, New York, USA, p. 228.

- Heery E, Kelly J, Waddington J (2003) Union revitalization in Britain. European Journal of Industrial Relations 9(1): 79-97.

- Sarkar S, Charlwood A (2014) Do cultural differences explain differences in attitudes towards unions? Culture and attitudes towards unions among call centre workers in Britain and India. Industrial Relations Journal 45(1): 56-76.

- http://alexwhite.org/2013/06/five-ideas-for-union-recruitment-ofyoung- people /

- Lawrence Jones A (2003) Trade unions and the internet, paper written for int unity.

- Balasubramanian G, Sarkar S (2015) Union revitalisation: A review and a research agenda. Research Gate, USA.

- Leischa (2010) Strategic use of ICT can revitalise trade unions. cyberunions.

- Lommerud K, Straume O (2007) Technology resistance and globalisation with trade unions: the choice between employment protection and flexicurity. Universidad do Minho NIPE Working Paper Series, Braga, Portugal.

- Mokyr J (1992) Technological inertia in economic history. The Journal of Economic History 52(2): 325-338.

- Marx K (1970) Wage labour and capital. In: Marx K, Engels F (Eds.), Selected works in one volume. Lawrence & Wishart, London, England.

- Bélanger M (2001) Technology organising and unions. In: Moll M, Shade L (Eds.), E-commerce vs. e-commons. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Canada.

- Darlington R (2000) The creation of the E-union: The use of ICT by British unions.

- Schradie J (2015) Political ideology, social media and labour unions: Using the internet to reach the powerful, not mobilize the powerless. International Journal of Communication 9: 1985-2006.

- Barbrook R (2000) Cyber-Communism: how the Americans are superseding capitalism in cyberspace. Science as Culture 9(1): 5-40.

- Heery E, Simms M, Delbridge R, Salmon J, Simpson D (2000) The TUC’s organising academy: An assessment. Industrial Relations Journal 31(5): 400-415.

- Nepgen A (2008) The impact of Globalisation on trade unions: Cosatu’s present and future engagement in international issues.

- Dahlber Grundberg M, Lundström R, Lindgren S (2016) Social media and the trans-nationalisation of mass activism: the role of twitter in trade union revitalisation. Peer-Reviewed Journal on the Internet 21(8): 2-3.

© 2018 Elsabé Keyser. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)